16th Anniversary Interview with

Founder & Executive Director Camilla Fox

In honor of Project Coyote’s 16th Anniversary, we are thrilled to share an interview below with Project Coyote’s Founder & Executive Director, Camilla Fox. In it, she shares her inspiration for founding this organization, some of Project Coyote’s achievements (and challenges) over the last 16 years, and what keeps her motivated to continue the often difficult work of wild carnivore advocacy. For over a decade and a half, Project Coyote has worked tirelessly to protect wild carnivores from unjust persecution and promote compassionate coexistence in diverse communities across the country. Please join us in celebrating this milestone and learning about Project Coyote’s history by reading Camilla’s words below. Thank you for being a part of this inspiring community – here’s to another 16 years of progress towards compassionate coexistence.

Camilla with her beloved Mokie in Tahoe

What led you to found Project Coyote?

I worked for the Animal Protection Institute for 10 years (now Born Free USA) from 1996-2006, where I began tackling issues around wildlife trapping, trophy hunting, and lethal predator control in the United States. It became apparent that there were few organizations that brought significant attention to the mismanagement of wild carnivores — particularly those species that have no state or federal protections and can often be killed year round in unlimited numbers. I also saw a need for proactive outreach to, and empowerment of, both urban and rural communities around coexistence with wild carnivores.

Concurrently, I had a desire to go back to graduate school to hone my schooling in wildlife policy, ecology, and conservation. I pursued my Master’s degree at Prescott College. Dave Parsons, former Director of the Mexican wolf recovery program for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, served as my graduate advisor. I was fortunate to have both Dr. Michael Soule (considered the father of conservation biology) and Dr. Adrian Treves serve on my graduate committee. It was during this time that I developed the idea for starting a nonprofit organization that would advocate for the most maligned, misunderstood and persecuted wild carnivores in North America, and provide communities with the information and resources they need to better coexist with them. Four months after graduation in 2008, I founded Project Coyote, and my graduate school committee members became our founding science advisory board. We opted to come under the fiscal sponsorship of Earth Island Institute, recognizing that we would have the administrative support of this excellent organization founded by one of my heroes: David Brower. I knew that the fiscal sponsorship relationship would allow Project Coyote to focus more of our time and resources on campaigns and programmatic work. We received a three year seed grant from the Leonard X Bosack & Bette M Kruger Charitable Foundation that helped provide the needed financial support to get us up and running.

How and when were you inspired to dedicate your life to protecting wildlife?

From a very young age, I had an affinity for wild nature and animals. I became a vegetarian when I was six years old after visiting my grandparents in northern England and visiting a nearby sheep farm. It was a bucolic farm in the Derbyshire moors and it was my first time getting to bond with baby lambs. That evening, we went back to my grandparent’s house, and I smelled an odd and unfamiliar odor wafting from the kitchen. I asked my grandmother what the smell was, and she said “lamb roast.” She explained that she was cooking baby lamb. I was horrified. I said to my family that I did not want to eat the baby lamb, and I never wanted to eat meat again and that was that. It wasn’t until my early 20s that I made the connection between animal cruelty and the dairy and egg industries after visiting various factory farms and decided to become vegan, now 30 years ago.

I am blessed to have had parents who instilled in me an appreciation for other beings, be they winged, furred or scaled. I’m also incredibly grateful that they allowed me to follow my own path, including my decision to not consume animals. My mother rescued and rehomed cats, and we always had many in the house — generally the “rejects,” too old or infirm for adoption. My father studied and taught canine ethology, the behavior domestic dogs, wolves, coyotes and foxes. We took in an orphaned wolf pup — a full Timber wolf — before her eyes opened, when she was just six days old.* She imprinted on us, and we became her pack for the next 14 years. It was an amazing and indescribable experience to grow up with a wolf; she had such intelligence, sensitivity, and awareness. We then adopted a scruffy two-year old dog from the St. Louis, Missouri animal shelter two days before he was due for euthanasia. We named him Benji, and he became fast friends with Tiny (our wolf).

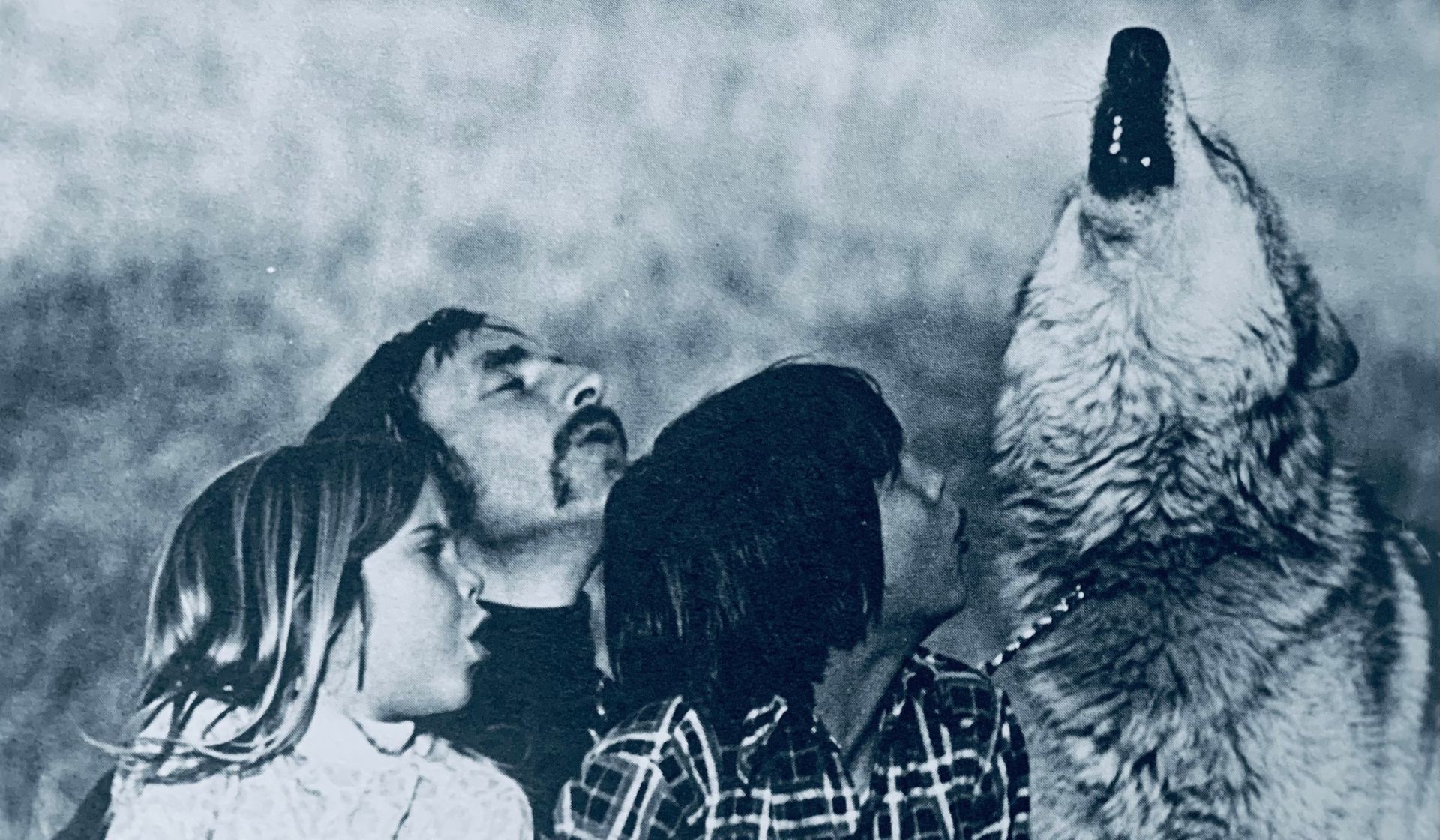

Camilla, brother Mike Fox Jr. and father Dr. Michael W. Fox enjoying an evening howl with Tiny (from Soul of the Wolf by Dr. Michael W. Fox)

The experiences I had with many individual cats and canines shaped my world. As did my love of exploring wild nature, including local ponds, fields, and pathways. I loved birds and insects, and was always drawn to the small and vulnerable, the sometimes discarded animals deemed common and insignificant by society. I could get lost in wondrous rapture with my head to the ground watching ants, bees, butterflies, and worms at work in my mother’s garden.

My love and deep connection to animals led me to question many societal norms and beliefs. I protested mandatory dissection in high school, arguing that it was not necessary to dissect frogs and pigs to learn about anatomy. My public high school finally buckled and I was able to pursue non-animal alternatives for my learning, which paved the way for future students who were opposed to dissection.

In college, I co-founded the Boston University Students for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, and after graduation, I took a job in California to work on farm animal policy reform. Since 1991 I have worked in both the animal and environmental protection movements, dedicating my life to making this a better world for animals and the Earth through non-profit organizations. I feel incredibly fortunate to be able to dedicate my life and passion to charitable work for the voiceless — for the underdogs — and to fostering Compassionate Coexistence and appreciation for wildlife and wildlands.

*Note: wolves do not make good pets. “Tiny” was orphaned when she was six days old and my father, as a wild canid ethologist, adopted her (the alternative and fate of her siblings was death). As a well-known author, speaker, bioethicist and animal advocate, my father has always condemned having wolves – or any wild animals – as pets – as does Project Coyote. You can learn more about our Protect America’s Wolves campaign that advocates for wolves in the wild – fully protected under the Endangered Species Act.

Camilla with Tiny in 1977

Project Coyote celebrates its 16 year anniversary in May this year. What accomplishments are you most proud of during this time?

I am most proud of the team we have built over our 16 years; not only our incredible staff but also our long-term volunteers, many of whom have been with us since inception. We have a very active member base as well, and I feel both pride and gratitude that we have continued to grow over the years without spending donor dollars on direct mail campaigns or acquisition mailing lists like so many other nonprofits do. While this has translated into slower growth, I think it has served us well as we have a very dedicated donor base with individual supporters and foundations that believe in our mission and our strategies for attaining our goals.

We have accomplished much in our 16 years of existence, especially on a relatively small budget. I think this is a testament to our team, their dedication and passion, and to the power of grassroots mobilization and coalition building for which we are known.

Each year we publish an impact report, which details these victories and accomplishments for wildlife so I won’t enumerate those here, but they can be viewed on our website.

Overall, I think each of these individual victories and successes highlights that we have helped raised the bar for wild carnivores in North America: increasing public awareness and appreciation for the critical role they play in maintaining healthy ecosystem and biodiversity- while also defending and protecting wild carnivores through legislation, grassroots mobilization, and litigation where necessary.

We now have highly functional coalitions across the country working together to better protect wolves, to ban wildlife killing contests, to ReWild parts of the continent with large carnivores, to protect and defend the Endangered Species Act and the species that critical act covers, and to reform state and federal wildlife agencies. Collectively, we are wielding more power within state legislatures as well as wildlife agencies, ensuring that wild lives are represented through our elected and appointed officials.

Red fox mother with kit | photo courtesy of Molly McCormick, #CaptureCoexistence Contributor

What are some of the greatest challenges for Project Coyote and for accomplishing the mission of the organization?

I think the greatest challenge we face in our wildlife advocacy work is one of culture and worldviews. We live in a country that still vilifies and unnecessarily persecutes wild carnivores — most recently demonstrated through the horrible torture of a female wolf in Wyoming. Overcoming this prejudice, hate and injustice is an uphill battle. At the same time, the public outcry that an individual story like this one has generated (not unlike the unconscionable murder of Cecil the lion in 2013 which garnered similar international outrage and a call for reform) reveals that human sentiments are changing with regard to our relationship to nonhuman animals, and with predators in particular.

We know through decades of research that large carnivores are critical to healthy and diverse ecosystems, and yet our laws and policies fail to recognize these values. The fact that so many carnivores can be lawfully killed in unthinkable ways in the U.S. (including trapping, snaring, trophy hunting, poisoning, killing contests, bounties, aerial gunning, denning, penning, and “predator whacking”) reflects a system and society that has failed to keep up with current science, ethics, and evolving public values.

Ultimately, we still live in a culture where human exceptionalism and speciesism plague western thought and behavior, as it has for centuries. It is a lens through which we justify incredible cruelty toward other species. This I believe is our greatest challenge. It is imperative to lift that veil and realize that we are not very different from the coyote or crow in our backyard, the whale or dolphin we admire on a whale-watching trip (or doing tricks for our entertainment, incarcerated in a small tank), the pig we consume as bacon on our plate. All of these beings communicate with one another, many of them form lifelong bonds with their mates, many of them express deep anguish when separated from one another. We must ask: how different are they from us homo sapiens who, until only relatively recently, descended from the trees to walk the savannahs, multiply and populate the Earth?

How do you stay grounded and connected to the wild lives you are working to protect?

Nature is my salve — or my church, as some would say. Every morning I stand outside to take sunlight in my eyes (important for the circadian rhythm!) and say hello to my local birds after their dawn chorus. I also have favorite walking trails not far from my house where my husband and I and our beloved canines find peace, equanimity, and beauty on a regular basis. Yoga, meditation, and flute playing are equally important rituals for me to stay grounded, connected, and internally joyful (and healthy).

When I need a more serious nature dose, I visit Point Reyes National Seashore — our own mini Yellowstone here in Marin County. Almost invariably, I see coyotes, bobcats, Tule elk and a plethora of birds (~490 bird species have been recorded in Point Reyes to date-,over 50% of the bird species found in North America). I always feel rejuvenated to my core after such an excursion, and ready for whatever heavy and sobering news may confront me in my Inbox.

But truly, I find daily joy in the small and wondrous in my backyard: the Anna’s hummingbirds (I have a resident male who I believe has staked out his territory around my home for many years, and we communicate to one other on a daily basis), the crows who gather at dusk in the baseball field across the road, the swallowtail butterflies that feed on my Salvia plants, the pair of great-horned owls who hoot-hoot in the evening. These connections not only bring me joy and comfort, but also remind me that the wild is not far from our homes, and can be tapped as a source of sustenance if one just stops, looks and listens.

While our work to defend wild carnivores can often be soul-sapping and quite depressing, I also find replenishment in the work itself: the daily sharing and strategizing with staff, volunteers and supporters; the building of communities and coalitions working towards our shared mission; and the knowledge that wild lives have been saved when a bill or rule passes that we have fought so hard to push through.

Camilla with rescued coyote Lichen at Lockwood Animal Rescue Center

When you look ahead to the next several decades, what is the world that you envision for wildlife and for our relationship to other animals and the Earth? Concurrently, what is your greatest hope?

I love this question as it’s not an easy one, but it’s one I contemplate every day. In general, I like to talk about possibility – what can we achieve in this short lifetime to make this a better place for all beings? What is the world we want to live in and what does it look like?

I focus on what we can do – not on what we can’t. I also look at history, and where progress has been made in human and societal evolution: the women’s suffrage movement, the civil rights movement, the inclusion of animal welfare considerations in our domestic animal laws. Of course, many of these laws are deficient; we still have yet to include wild animals in our anti-cruelty statutes and domestic animals are still regarded as “property,” denying them interests and rights of their own.

I find inspiration in learning from past achievements. What have we done right? What lessons can we learn from these advances in moral and societal progress? How can we do better? And then I look at the pockets of change, both nationally and internationally, where we are making progress: for example, recognizing the rights of other beings and ecosystems, like great apes in New Zealand and rivers in Ecuador. These achievements are a testament to advances in our collective consciousness about what it means to be human in a world shared with others — be they conscious and sentient or not — but who collectively sustain our Earth and ensure healthy functioning ecosystems that we all depend upon.

They also reflect what is possible when people organize, educate and lobby for systemic reform. As Margaret Mead, a 20th Century anthropologist who changed the way Western society views primitive cultures, so eloquently said:

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

I believe in this sentiment; I believe that so many of our most radical and important movements started with small groups of individuals organizing around a shared passion, a strategic mission, unified values and vision.

Relatedly, Project Coyote has undergone a process of reviewing and refreshing our mission, vision and values. I’m heartened – and hopeful- by both the process and the outcome. Our mission has only changed slightly with the inclusion of coalition building as part of our mission- which we view as essential to achieving our vision.

Mission: To protect North America’s wild carnivores and promote compassionate coexistence through education, science, advocacy, and coalition building.

Vision: A North America where humans and wild carnivores coexist and ecosystems thrive.

A vision morphs in time, reflecting shifting values and ethics, and we will continually revisit this, as well as our values, as I think all institutions and nonprofits should periodically do.

Ultimately my hope is that we can expand our circle of compassion to include all sentient beings, that we begin to recognize and see other animals, be they furred, finned, scaled, or winged, as individuals with their own intrinsic worth, interests, emotions, and desires. When we reach that state of presence, attention, empathy, and awareness, we will be in a state of Compassionate Coexistence and our relations and behaviors with others will reflect as such. I’m also heartened and hopeful with new research coming out about animal intelligence, emotions, sentience, and interspecies communication (see: The Internet of Animals: Discovering the Collective Intelligence of Life on Earth by Dr. Martin Wikelski). I believe this kind of research, focused on demonstrating that every animal is an individual deserving of respect and dignity, could be a game-changer. That is my hope.

To quote some of my favorites on this topic, which I feel are worth repeating:

“Hope is the active conviction that despair will never have the last word.”

~Senator Cory Booker

United: Thoughts on Finding Common Ground and Advancing the Common Good

“Ultimately an attitude of reverential respect for life and for the environment will benefit humanity, since it is the basis for a just and sustainable society.”

~Dr. Michael W. Fox

The Boundless Circle: Caring for Creatures and Creation

“A thing is right when it tends to advance the beauty, stability, integrity of the natural community… there are those who can live without wild things and sunsets, and there are those who cannot.”

~Aldo Leopold

“Something will have gone out of us as a people if we ever let the remaining wilderness be destroyed … We simply need that wild country available to us, even if we never do more than drive to its edge and look in.”

~Wallace Stegner

The Sound of Mountain Water

“We will recover our sense of wonder and our sense of the sacred only if we appreciate the universe beyond ourselves as a revelatory experience of that numinous presence whence all things came into being. Indeed, the universe is the primary sacred reality. We become sacred by our participation in this more sublime dimension of the world about us.”

~Thomas Berry

The Great Work: Our Way Into the Future

“Hope is often misunderstood. People tend to think that it is simply passive wishful thinking: I hope something will happen but I’m not going to do anything about it. This is indeed the opposite of real hope, which requires action and engagement.”

~ Jane Goodall

The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times

“Truth and beauty can still win battles. We need more art, more passion, more wit in defense of the earth.”

~David Brower