Red River War: An Instrumental Journey Through the Last Major Conflict on the Southern Plains

By M. Walker

About a year ago, I joined the Project Coyote team via the Artists For Wild Nature program, introduced myself, shared a unique conceptual instrumental album I had just released, and then promptly got to work composing and recording another instrumental record. Released January 8, Red River War is a spiritual successor to my previous work, Canyon, Illuminant. The instrumental music in this piece explores significant historical events in the same canyon system and high plains of the Llano Estacado where the last album was set. The setting here has jumped considerably in years, from the pre-sapien drama of megafauna living on the Southern Plains, which we previously explored, to the last major military conflict between the United States Army and several Plains Tribes.

This war, later called the Red River War, was fought between the US Army and warriors of the Kiowa, Comanche, Southern Cheyenne, and southern Arapaho tribes, beginning in the summer of 1874 through the spring of 1875. Fighting erupted at the confluence of the United States federal government’s continual defaults on legal obligations to those tribes, dictated by the Treaty of Medicine Lodge of 1867. After the dissatisfied factions of the tribes on newly formed reservations departed back to their traditional hunting grounds and ranges on the Llano Estacado, they found themselves in the face of starvation amidst severe drought and lack of game. The US army had conveniently turned a blind eye to buffalo hunters’ decimation of the bison population of the southern Plains, again in clear violation of ratified treaty.

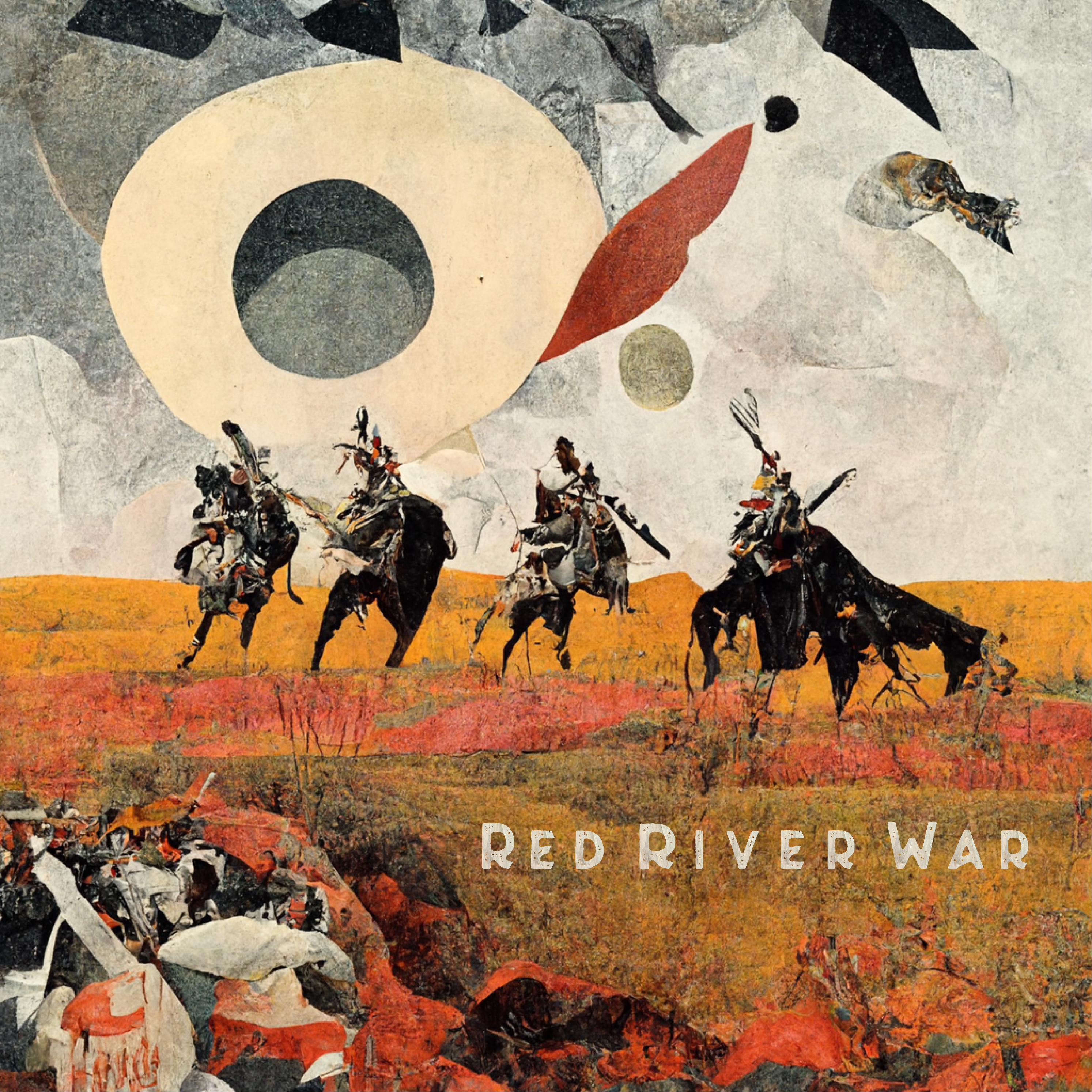

Album cover for Red River War

From the start, I was intimidated by composing music about a topic with so much gravity. This war was complex and relatively unknown, even to the folks who live on the land where it took place today. But I felt it was really important to create a piece of art that explores such an important war which so few know about. It felt important to tell the story that founded the place where I was raised. As I began unpacking this concept as an artistic subject matter, I had to dig into what feels like an obviously incomplete and deeply problematic historical record.

Setting out to create a narrative from the facts, I had no idea how to accurately tell the history. I am not an historian. The more I examined my lack of credentials or bonafides, the more I realized that this composition was not meant to be a historical record anyway. So I decided to look at other elements of the time and place. Subjectively, this war was an immense story of ambition, pain, and the human struggle for survival. There were incredible personalities on display. There were unbelievable ecological changes rooted in the circumstances on the high plains in the late 1870s. There were terrifying battles in this war. There were moments in which the human condition bore its teeth for history to examine. All of it occurred in the ocean of prairie grass and canyon wilderness that I call home. This album is a musical treatment of the story of the Red River War; the places, animals, battles, destruction, sentiments, and significant characters that crossed the Texas Panhandle in 1874.

Of course, beyond telling the stories of the complex and fascinating human characters involved, I kept coming back to the catalyst of the war – the decimation of crucial animal species on the high plains. After all, the fighting started at Adobe Walls, where the most prolific of bison hunters were camped. When I realized how important this thread was as I noticed it pulled through each chapter of the saga, I knew I had to emphasize its prominence. So I decided to open the album with a piece about the feeling of desperation after realizing the extent of the bison killings.

“Between July 1 and September 1, 1873, the Cators killed nearly 7,000 buffalo and had in their employ seven skinners. When the Panic of 1873 caused the price of hides to drop momentarily, the Cators took up “wolfing” and killed over 600 gray wolves and coyotes for bounty.”

— H. Allen Anderson in his bibliography of just one buffalo hunting family, the Cators in Palo Duro

“[The bison hunters have] done more in the last 2 years to settle the vexed Indian question than the entire regular army had done in the past 30 years. They are destroying the Indian’s commissary. Send them powder and lead if you will, but for the sake of lasting peace let them kill, skin, and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated. Then your prairies can be covered with speckled cattle and the festive cowboy, who follow the hunters as a second forerunner of an advanced civilization.”

— General Philip Sheridan addressing the Texas Legislature

As the bison population dwindled to near extinction and westward colonial expansion continued at a full gallop, other species which once enjoyed the bounty that the canyonlands had to offer were relegated to migration. Of course, attitudes toward predator species in the late 1800s created the conditions for the very policies that we feel the echoes of even today. One of the most fascinating accounts of wildlife migration I have ever seen were also associated with the canyonlands and with the Red River War.

“Early one morning… I was riding along the edge of the Plains a short distance from the cap rock when I saw a long string of objects coming out of the canyon and heading in a northwesterly course across the Plains. Anxious to see what it was I hurried along and soon got close enough to see to my astonishment that they were gray wolves. It was, of course, impossible to ascertain the number with any degree of accuracy, but there must have been several thousand of them… I rode up to within a few yards and began shooting into them with my pistol, but thus created no consternation in their ranks, nor did they do as hungry wolves are supposed to always do – stop and devour such as were killed or crippled.”

— Don H. Biggers

As I imagined such a wild sight, thousands of wolves moving across the prairie landscape, I visualized what it might have felt like to be in an army camp next to the fire, hearing the sounds of coyotes and wolves beyond sight in the dark night. I read that the tune for John Brown’s Body was a popular song amongst soldiers after the civil war and figured somewhere in a saddle bag must have been a fiddle and its owner barely able to scratch out a melody. So I took some field recordings of horses and coyotes, used synthesizers to create the sound of wind and a crackling, and even some abstract bowing on my fiddle to create coyote yelps, and created a soundscape of a US Army camp on the prairie. This was the backdrop to my very basic rendition of the homage to the old abolitionist, played near a crackling fire amidst the snorts of horses and howls of wild canids in the darkness. I wanted the listener to feel that they were there.

“Old John Brown’s body lies-a mouldering in the grave,

While weep the sons of bondage whom he ventured all to save;

But though he lost his life in struggling for the slave,

His truth is marching on”

— Lyrics from John Brown’s Body, a popular abolitionist tune sung by the US Army during the Civil War

I could feel the irony of this all too powerful song (which eventually became the melody for The Battle Hymn Of The Republic) played by the very same Army which set out to end chattel slavery as they set out to eradicate a continent of its inhabitants by virtue of an imagined manifest destiny. It felt like a moment of contradiction that I could not pass up, even if its imagining was purely fictional.

“We had every reason to believe that the hostiles, eluding the column sent there, might seek and follow our trail, with a large body; if so, our little handful of men would, it was feared, have made a feeble resistance if attacked. At night the wolves came out of the “bottoms” and numerous coulees, arroyas, and ravines, in countless numbers and besieged this camp. The sick and wounded became very nervous, for in their boldness the ravenous animals advanced to within a few feet of our tents in their eagerness for the meat which we had hung all about us in large quantities for immediate use, besides the carcasses scattered here and there had attracted their scent, and in the glare of the campfire their long, white teeth could be distinctly seen, as they tumbled, fought, and howled over their canine feast… No such number of wolves had ever been seen or heard by us in that country.”

— Lt. Robert G. Carter

It’s striking to read soldier’s accounts from this military campaign, both in descriptions of their adversaries and of the megafauna they encountered. Many viewed them exactly the same, diminishing the value of their lives and fundamentally calling into question their right to exist in their ancestral lands. What those soldiers didn’t realize was that the comparison of indigenous peoples to wolves was one of the finest compliments they could have paid. Unfortunately, there is still much to be done to change public perception such that we all understand the compliment.

These are heavy subjects on which to contemplate and create art. I did my best to be fair and truthful, while also creating a sense of the landscape and times to bring those events to life. With this project, I hope to begin a journey with each of you who encounter it. There are uncomfortable histories to reckon with. There are realities we have yet to connect with. There is mystery even beyond what we know about the place and time when the war was fought. But in all of it, I hope that you see the high water mark of biodiversity in what is now inappropriately considered by many to be “fly-over-country.” This is not a coincidence – it is a direct consequence of the American government’s policies and actions. It is a direct consequence of unfettered trade and resource extraction. It is a direct consequence of the insatiable hunger for land which we may all too conveniently ignore in our modern world.

I hope this work illustrates for you the impact of our encroachment on biodiverse habitats. The animal life on the High Plains (that we can now only imagine) once paralleled the African Serengheti. It can be so again if we want it to be. But as with the biggest challenges of our time, the problems we face are not technological. They are cultural and social. They derive from a lack of will amidst a system of profit and conquest that has carefully told stories of glory and victory.

I hope that you make the conscious choice to tune into a different story and explore what profound possibilities exist when we imagine a future which our descendants can be proud of.

M. Walker is a Project Coyote Artist For Wild Nature from Amarillo, Texas. He is a musician, musical producer, painter, flower arranger, photographer, and writer. Learn more about his work here.