Notes From The Field Blog by Ryan Pickerill

In human-dominated landscapes, landscape architecture can be an important conservation tool.

When you think about wildlife conservation, you may think of national parks and nature preserves. While these protected areas and public lands are definitely important, conservation increasingly occurs at the landscape scale across a mosaic of land uses and private and public lands. Animals often don’t live their whole lives in the confines of a preserve. Some establish home territories much larger than the size of a single protected area. Others may not have a specific home territory, but move between patches of appropriate habitat. Individuals and groups will leave a patch in search of resources, mates, or territory. All of this is vital for the long-term survival and genetic diversity of a given species. Yet the human-dominated landscape that usually surrounds wildlife habitat presents significant obstacles to animal movement. In particular, linear infrastructure, like roads and railways, forms barriers that can be near to impossible for wildlife to cross safely.

I originally got into landscape architecture because I liked computer games where you could design theme parks and zoos. While studying landscape architecture as an undergraduate, however, I started to develop an interest in design for the purpose of wildlife conservation. Could we treat wild animals and plants as the clients of a design project? This idea led me to focus on landscape architecture as a conservation tool in my master’s degree program, and eventually to intern with Project Coyote.

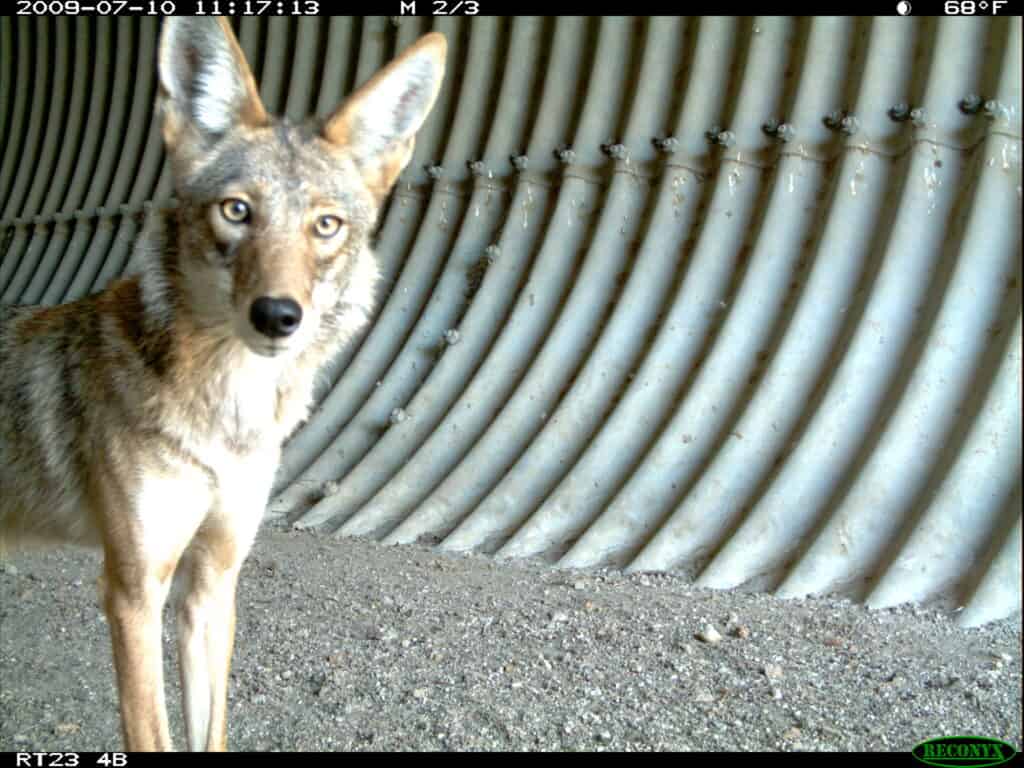

Coyote crossing through a parking lot in Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area | public domain photograph

What are some of the ways in which landscape design and conservation intersect? Adapting urban environments to fit the needs of wildlife is one. We can design gardens with native plants and nesting opportunities for pollinating insects, birds, and bats. We may also create green corridors that help animals safely move through urban areas. We may even design habitats for fish in urban rivers. Rewilding – where previously disturbed land is turned back into habitat – is another way. Agriculture, parking lots, and other human land-use patterns are barriers for many species, so rewilding is a way to reestablish connectivity. At Project Coyote, I’m helping the Heartland Rewilding initiative, which aims to reconnect habitat in states along the Mississippi River. Even if we rewild corridors, however, they are often still fragmented by linear infrastructure. That’s where another landscape design solution comes in: crossing structures.

Loess Hills National Scenic Byway, a focal region of Heartland Rewilding | photograph by Lance Brisbois

You may have seen pictures of the land bridges built for wildlife in Banff National Park in Alberta, Canada. These are just one type of crossing structure. Crossing structures may be large, like an underpass built for elephants in Kenya, or small, like a little metal bridge made for crabs on Christmas Island, Australia. They may go over infrastructure, like overpasses for wolves in Poland, or under, like the culverts used by everything from elk to coyotes and badgers in the western United States.

In the Midwestern United States, crossing structures tend to be small and go under roads. For example, a culvert in Portage County, Wisconsin, was built for turtles to travel between a lake and wetland separated by a busy road, while a program in Missouri is helping to convert low water crossings to bridges under which aquatic species can more easily pass. Since, in most Midwestern states, white-tailed deer are the largest wild animal and they often do not follow predictable migration patterns, large crossing structures typically aren’t built for wildlife. Also, it is difficult to secure funding for a crossing structure unless both sides of the road or railway are permanently protected from development. But Midwestern states can – and often do – adapt existing bridges and culverts to make them more friendly for deer and other wildlife to cross roads.

Trail camera capture of a coyote in a culver in Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area | public domain photograph

As the Heartland Rewilding initiative makes more progress, states may need to provide safe crossings for formerly absent species as they move back in. While we can’t predict the placement of these structures just yet, we can identify tools that will help to decide where they should be built once large animals are present. In the meantime, we can also look at existing crossing structures as well as information about these species and their relatives in order to create guidelines for how these structures should look and function. As a graduate student, I worked on a project that aimed to do this for tigers, elephants, and rhinos in Nepal whose habitat was going to be split by a new railway. Now, I’ve done similar research in the heartland of the United States. The short report I compiled will help inform Heartland Rewilding’s efforts to connect the heartland. Small rewilding and species reintroduction efforts are already underway in many states. Additionally, while large dedicated crossing overpasses may not be feasible in the near future, many precedents exist for adapting existing drainage infrastructures and bridges to make them permeable for wildlife. It’s an exciting look forward at how the Midwestern landscape could change in the future, and how more positive relationships between humans and animals may be developed.

Ryan Pickerill was a 2022 summer intern with Project Coyote and is a recent Master of Landscape Architecture graduate from the University of Michigan School for Environment and Sustainability.

Interested in interning with Project Coyote? We are currently accepting applications for Programs & Campaigns Interns for summer 2023. Please check our employment page to learn more and apply.