American Bears

ECOLOGY OF THE AMERICAN BLACK BEAR (URSUS AMERICANUS) AND GRIZZLY BEAR (URSUS ARCTOS)

Evolution

The fossil record of the bear family (Ursidae) began to appear in the Miocene Epoch around 23 million years ago (Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2018, Burt & Grossenheider 1976, Nowak 1999). Since that time, bears have evolved to become the largest living terrestrial carnivore on the planet (Burt & Grossenheider 1976). Currently, there are eight extant species of bears on the planet (“Bear” 2019). North America is home to three different species of bear: black bears (Ursus americanus); brown bears, also called the grizzly bear (Ursus arctos); and polar bears (Ursus maritimus). This page features black and grizzly bears.

Distribution

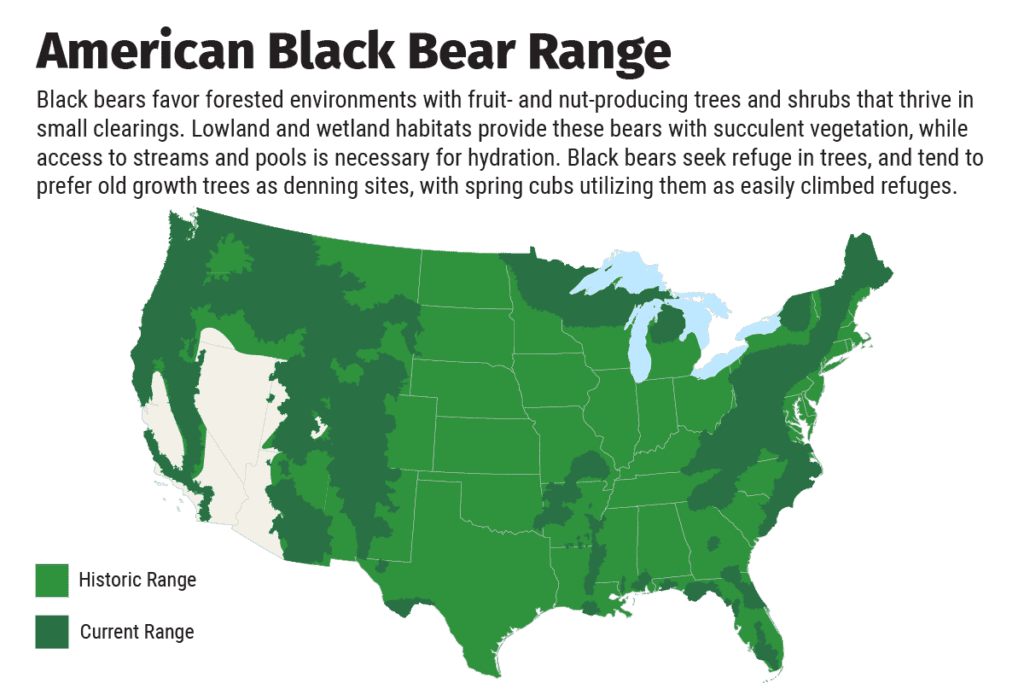

Black Bear Distribution

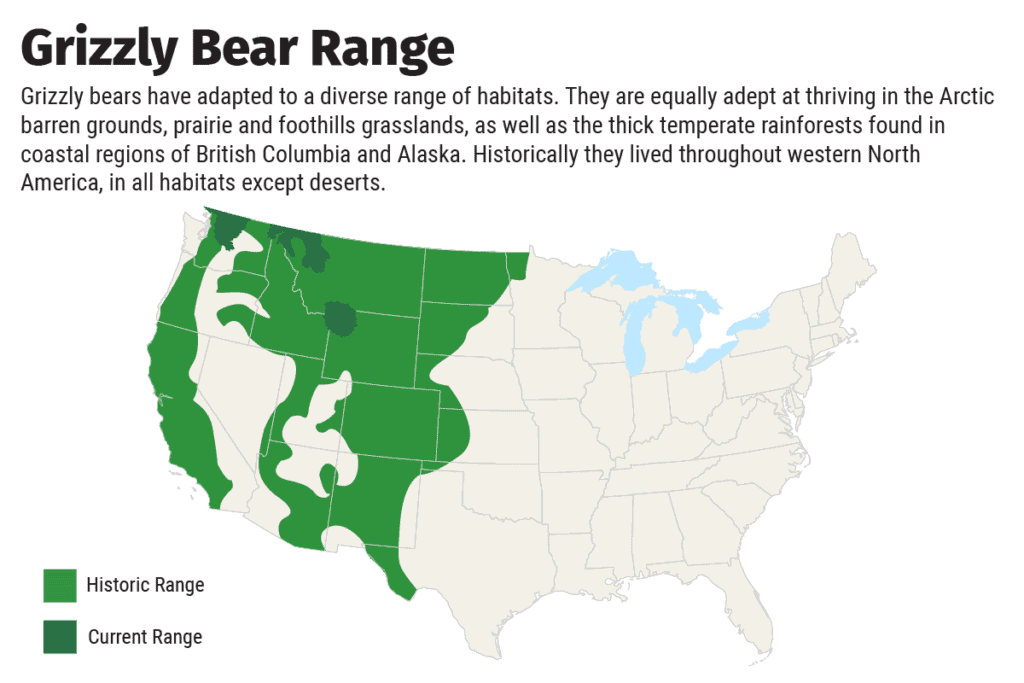

Grizzly Bear Distribution

Historically, grizzly bears in North America ranged from Alaska to Mexico and from the Pacific Ocean to the Great Plains (“Grizzly Bear” n.d.; Mattson & Merrill 2002, Nowak 1999, Schwarts et al. 2003). Today, grizzly bears’ home ranges have greatly diminished. In Canada, they are found in Alberta, British Columbia, Yukon, and the Northwest territories (Waits et al. 1998). In the U.S., their range includes Alaska, and small areas of Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, and Washington (“North America’s Bears” n.d.; Waits et al. 1998). The United States listed grizzly bears as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1975. In Canada, great concern surrounds the health of grizzly bear populations, leading some provinces to list them as threatened (Schwartz et al. 2012).

Grizzly bears along the coastal areas of Alaska and Canada are often much larger than average, leading scientists to further separate them into distinct geographic sub-species. These larger bears are called Kodiak bears or Alaskan (big) brown bears (“North America’s Bears” n.d., Burt & Grossenheider, 1976, Nowak 1999). Furthermore, the smaller grizzly bears who manage to survive the cold, treeless wilderness in Canada’s western arctic are called barren ground grizzly bears (Struzik 2006).

Habitat

Black Bear Habitat

Black bears are commonly found in habitats filled with thick vegetation, possibly because black bears evolved alongside other bear species, like the extant grizzly bear and the extinct giant short-faced bears, as well as other larger predators, that were more aggressive and dominated open habitats (“American Black Bear” n.d.). While most black bears populate areas distant from human activity, some can be found in vegetated habitats close to urban areas.

Throughout most of the U.S., American black bears inhabit mountainous regions at elevations of 1,300 to 9,800 feet (“American Black Bear” n.d.). The habitat for black bears found in Mexico and southwest America include pinyon juniper woods and chaparral stands, with bears going into the open to consume prickly pear cactus (“American Black Bear” n.d.). In the southern Appalachian Mountains, American black bears are mainly found in mesophytic and oak-hickory forests, while in the southeast coastal regions, bears can be found in bays, flatwoods, and swampy hardwood areas (“American Black Bear” n.d.). Beech, birch, maple and coniferous species populate the forest that American black bears commonly inhabit in the northeastern portion of North America, along with swampy areas with white cedar (“American Black Bear” n.d.). In the Rockies, American black bears can be found in spruce-fir forests as well as subalpine ridgetops, burns, sidehill parks, roadsides, wet meadows and riparian habitats (“American Black Bear” n.d.). On the Pacific coast, the American black bear inhabits areas with Sitka spruce, redwood, and hemlocks (“American Black Bear” n.d.). However, important areas within these habitats for American black bears include successional areas, such as wet and dry meadows, high tidelands, brush fields, riparian habitats, and different mast-producing hardwood species (“American Black Bear” n.d.).

In places like Canada or Alaska that have less human development, American black bears can be found in lowland regions, sometimes in semi-open areas, which is typical habitat for them without competition from polar bears or grizzly bears (“American Black Bear,” n.d.).

Grizzly Bear Habitat

Social Structure

Bears are sentient, self-aware and social animals, with distinct cultures and personalities. They are generally described as solitary by nature, except for females with young and congregations of bears at sites with large caches of food. Consequently, a large majority of a bear’s life is sometimes spent wandering alone or hibernating. This does not mean they are asocial or do not have social interactions with other bears. For example, studies have documented social behavior in grizzly bears that reveal bears can spend a large amount of time interacting with others (see Stenhouse et al. 2009). There is increasing evidence that bears have a social system characterized by matrilinear assemblages and related females’ use of a largely exclusive common area (Støen et al. 2005, Kilham & Spotila 2022), which supports an organized society.

Dominance hierarchies are often formed amongst familiar bears, especially if a large amount of food is concentrated in one area. Matriarchs often show dominance behaviors over subordinate females. Some bears seemingly get along better with other bears while some do not tolerate each other. Contrary to how they are sometimes portrayed, they are usually peaceful animals who try to avoid conflict even among themselves. (Kilham & Spotila 2022, Nowak 1999, Stonorov 2000, as cited in “Behavior” n.d.). They can coexist with other bears and create friendships or partnerships with each other, and even share food (Støen et al. 2005, Kilham & Spotila 2022, Stonorov 2000, as cited in “Behavior” n.d.). Some unrelated adults even teach younger bears skills such as where to acquire resources (Hopkins III 2013) .

As winter approaches, bears begin to gain weight until it is time to hibernate. Both black and grizzly bears undergo true mammalian hibernation. Hibernation is an adaptation to seasonal food shortages, low temperatures and snow cover on the ground. The physiological processes of hibernation can differ depending on the species of mammal. With bears, respirations decrease from 6-10 breaths per minute to one breath every 45 seconds; metabolic rate is decreased 50 to 60 percent; heart rate drops from 40-50 beats per minute to 8-19 beats per minute; and body temperature drops from 38 degrees Celsius to 31 degrees Celsius. Both grizzly bears and black bears do not eat, drink, defecate, or urinate during hibernation. In order to survive during this long slumber, they live off the fat stores in their body which depletes up to 15-30% of their body weight. Furthermore, waste products are recycled when urea is catabolized into nitrogen. This nitrogen is used to build protein for maintaining muscle mass and organ tissue (USNPS 2015).

Other physiological processes are also altered while bears are sleeping. For instance, bears continue to produce feces during hibernation; however, the feces will form a plug in the anus to prevent the bear from defecating in the den site. Also, while most mammalian species experience osteoporosis from being in a non-weight bearing position for an extended period of time, bears do not. Furthermore, a bear’s cholesterol will double during hibernation; however they don’t suffer from the same hardening of the arteries or gallstones as a human would during this period of hypercholesterolemia (USNPS 2015).

Black Bear Social Structure

When not hibernating, black bear behavior is linked to plant growth, fruiting, and availability of food. They tend to avoid other bears and will often defend their territory from unknown intruders, such as unrelated individuals. Other black bear behavioral characteristics include the display of a variety of vocalizations including a “woof” sound when startled, a loud growl when fighting, or a shrill howl by cubs when lonely or frightened (Burt & Grossenheider 1976, Nowak 1999).

Female black bears reach sexual maturity at the age of four to five years and males reach sexual maturity between five and six years of age. Mating season usually peaks between June and mid-July. Females are in estrus for only 1-3 days during this time and generally give birth every other year but sometimes wait 3-4 years. Pregnancy lasts 220 days,however, delayed implantation causes embryonic development to start in the autumn and lasts only ten weeks. Births occur in January and February, often during hibernation (Nowak 1999).

Depending on the climate of a particular area, black bear hibernation can occur as early as late September and can last into May. Their sleep is only interrupted by an occasional journey out of their den during periods of warm weather. Den sites are usually composed of fallen trees, hollow logs or trees, or burrows. Litter size in black bears can range from one to five cubs. Young bears are born with their eyes closed. Weaning occurs around 6-8 months (“Black Bear” n.d., Burt & Grossenheider 1976, Nowak 1999).

In order to avoid aggressive adult males in the breeding season, the mother and cubs will depart the den site in the spring. Cubs will remain with their mother into the second winter. Mothers usually tolerate their offspring within their territories and will allow their daughters to incorporate portions for their own. Young males disperse an average of 61 kilometers from their birth areas. Black bears can sometimes live 30 years or more (BearSmart.com n.d., Burt & Grossenheider 1976, Nowak 1999).

Grizzly Bear Social Structure

Barring the aggressiveness shown in dominance hierarchies, there is no indication of territorial defense amongst grizzly bears. They will even form family foraging groups of multiple ages where food is plentiful. Female grizzly bears have much smaller home ranges than males but also show the most aggression when they’re with their young. Large adult males are mostly avoided in gatherings and will sometimes kill young bears. The least aggressive bears in the dominance hierarchy are the adolescents (Stonorov 2000, as cited in “Behavior” n.d.; Nowak 1999).

During breeding season, male grizzly bears will fight over females. The winner will breed with the female for 1-3 weeks. Mating takes place from June to July with delayed implantation. The fertilized egg will begin development sometime in October or November. Birth occurs between January and March during hibernation. Each litter can have as few as one cub and as many as four. Cubs are born with their eyes closed. Each cub is weaned at five months and remains with the mother through multiple springs (usually no less than two and no more than four). Siblings will often maintain social interactions for several years after leaving their mother. Sexual maturity for both genders is between the ages of four and six. Grizzly bears can sometimes live well past 30 years of age (Nowak 1999).

Grizzly bear hibernation begins in October and can last through May depending on the locality, weather and the health of the bear. In some southern areas hibernation does not occur. Their dens are made of dry vegetation and usually dug by the bear. Preferred locations are on a sheltered slope under a large rock or under the roots of large trees. These sites are used year after year (Nowak 1999).

Even though grizzly bears prefer more open terrain, they often shelter in dense cover during the day when wandering or foraging. As evening approaches they begin to move and feed, staying active through early morning. The larger bears in coastal Alaska are active throughout the day. Seasonal movements are common in grizzly bears and coincide with food sources like salmon and areas with high berry yield (Nowak 1999).

Appearance

Black Bear Appearance

Grizzly Bear Appearance

Diet

Black Bear Diet

Three quarters of the black bear diet is composed of fruits and vegetables. This includes fruits, berries, honey, tubers, nuts, acorns, grass, sapwood, and roots. The other twenty-five percent of their diet consists of insects, fish, rodents, carrion, eggs, and occasionally other larger mammals. Black bears also commonly consume garbage from dumps (Burt & Grossenheider 1976, Nowak 1999).

Though mostly nocturnal, black bears are frequently active at all hours when foraging (“Know the Difference” n.d., Burt & Grossenheider 1976, Nowak 1999).

Grizzly Bear Diet

During the early spring, grizzly bears forage for overwintered berries, grasses, sedge, roots, mosses, bulb and other starch rich foods, using their long claws to dig when necessary (Tighem 1997, as cited in “Food and Diet” n.d., Burt & Grossenheider 1976, Nowak 1999). As the season progresses this changes to succulents, and perennial forbs. By autumn, berries, bulb and tubers are a main component. In addition to plants, their diet includes ants, beetle larvae and other insects, mice, ground squirrels, marmots, and carrion. Grizzly bears of the Canadian Rockies hunt moose, elk, caribou, mountain sheep, and mountain goats. The grizzly bear is also a competitor with, and predator of, black bears where ranges overlap (Tighem 1997, as cited in “Food and Diet” n.d., Nowak 1999).

The contrasting size of Alaska and Pacific Coast brown bears and the smaller grizzly bears of interior North America can be attributed to a diet of anadromous salmon, which is higher in protein and fat. This diet allows them to grow larger than anywhere else in their range (Nowak 1999) Coastal bears congregate at greater densities in areas where salmon migrate upstream.

Even though grizzly bears appear slow, they can move very quickly, easily overtaking a black bear on the run (they have been found to reach speeds greater than 30 mph/48 kph with a top speed of 37 mph/59.5 kph) (“Dispelling Myths” n.d., “Grizzly Bear” 2015, Nowak 1999). They are also extremely strong. Some eyewitness accounts discuss horse and bison carcasses being dragged considerable distances. However, their claws and feet are not adapted for climbing trees like black bears (Nowak 1999).

THREATS TO BEARS

Due to their large size and distinctive behavior, bears have unique challenges that can make surviving difficult and sometimes tragic. Currently, the largest threats to North American bears are humans and rural development (Schartz et al. 2012). During the nineteenth century, wide-spread poisoning of bears and other large carnivores with strychnine was common as people expanded west (Young & Jackson 1978). Humans continue to kill or intensively control bear populations for a multitude of reasons including fear, sport, cash-crop protection, black-market trading, food, and predation on domesticated animals. Fortunately bear predation on cows and sheep is minimal; however, they do extensive damage to cornfields and other crops like oats and sunflowers (Nowak 1999, Taylor & Phillips 2020). Another source of conflict between humans and bears is the attraction of bears to urban food sources, especially when combined with habitat degradation, developments, recreational killing, and poaching for the medicinal use of bear parts for export to Asia, and human encroachment through activities like logging, mining, oil and gas drilling and other (Bigwildlife.org 2008, Nationalgeographic.com 2010, Nowak 1999).

As urban centers grow and encroach into rural settings, garbage collection centers and dumpsites have become more commonplace near bear habitat. Human-made waste threatens bears in a multitude of ways since edible garbage has been documented as a common food source for bears and has served as an attractant in developed areas (Mathews et al. 2003). Firstly, the risk of mortality for bears through direct or lethal management actions and bear-vehicle collisions is higher when they forage in and near urban areas (Merkle et al. 2013). Since bears are opportunistic foragers, they will often risk conflict by traveling into urban centers when garbage is readily available. This increases the risk of human-bear conflicts, especially in many National Parks where encounters between visitors and bears often arise due to human noncompliance with posted restrictions, such as feeding or approaching bears. A secondary threat from human development is traffic accidents as bears cross highways and roads to reach natural food caches and human generated food sources (Mathews et al. 2003, Merkle et al. 2013, The Wildlife Team 2003). Roadways, particularly ones with higher traffic volumes, can negatively affect wildlife populations through direct mortality and habitat fragmentation (Sawaya, et al. 2012). A related issue is the general assumption that bears found around developed areas are food-conditioned, although that is not necessarily the case (Hardeman et al. 2023).

Since bears maintain large home ranges, habitat fragmentation by roadways, highways, and other thoroughfares is of particular concern to ecologists. Although accident mortality of bears on highways, streets, and roads is worrisome, researchers have found that barrier effects caused by road avoidance are a much larger ecological problem. For instance, one study indicated that wide ranging, large bodied carnivores such as black bears and grizzly bears are susceptible to road-caused population fragmentation due to their low densities, low reproductive rates and large home ranges. In an effort to address this problem, some government run parks, reserves, and wildlife refuges are building land bridges or wildlife crossings to create wildlife corridors for safe travel within fragmented habitat (Sawaya, et al. 2012).

One of the more tragic threats to bears, especially black bears in North America, is the hunting, killing, and black market trade of bears and their body-parts to various parts of Asia. Unfortunately, the decline of the Asiatic black bear has sparked increased pressure on black bears, and other bears globally, for body parts used in traditional medicines and foods. Prized black market bear products include meat, fat, paws, bones, brain, blood, spinal cord, head, skin, and gallbladder. The gallbladder is a valuable commodity used by many cultures to treat diseases of the liver, heart, and digestive system, as well as to relieve pain, improve vision, and clean toxins from the blood (Nowak 1999). Some dried bear gallbladders can sell for as much as thirty thousand dollars (Bigwildlife.org 2008). Currently, thirty-four states in the U.S. have bans on the trade of bear gallbladders and bile. (Nationalgeographic.com 2010, Bigwildlife.org 2008).

ECOLOGICAL ROLE OF BEARS

Both black bears and grizzly bears are considered apex predators and top-down co-regulators of the food web through their direct (e.g., consumption) and indirect (e.g., effect on behavior and distribution of other beings) effects. Some scientists label them as keystone species as they contribute to nutrient cycling of salmon and carrion, indirectly assist with seed dispersal over large areas, regulate prey species such as ungulates (which in turn leads to increased plant biomass), and assist with soil aeration when digging for roots and rodents. Without keystone species such as bears, the health of our ecosystems would decline – affecting forest regeneration, clean water, natural pest control, seed dispersal, disease regulation, climate regulation, etc. (Davidsuzuki.org, 2014; Harrer & Levi 2018; Keystoneconservation.us, n.d.; Predatordefense.org, n.d.; Willson 1993).

TIPS AND TOOLS FOR COEXISTENCE

If you live in an area that has black bears, grizzly bears, or a combination of both as part of the surrounding ecosystem, there are numerous steps you can take to reduce conflicts associated with these species. In addition, various advocacy groups can offer advice on reducing encounters, preventing conflicts, and purchasing equipment to protect domesticated animals and other cash crops from bear damage. If you are a rancher, these organizations will guide you in non-lethal deterrence methods and you may receive compensation for domesticated animal losses (Defenders.org 2012).

Following the coexistence tips below can help protect your property, pets and family (see Dietsch et al. 2018, ncwildlife.org n.d., Marlet et al. 2017, Northrup et al. 2023, Schwartz, et al. 2012, Westernwildlife.org n.d.):

- Store trash in a secured location

- Remove bird feeders when bears are in the area

- Remove fallen fruit from under fruit trees

- Don’t eed pets outdoors

- Clean all food and grease from barbeque grills

- Use electric fencing to secure crops, animals, and beehives, or modify their placement or configuration

- Eliminate pungent food odors from your residence

- Promote the use of bear resistant dumpsters in your communities

- Discourage the feeding of bears by visitors, tourists or neighbors

- Educate yourself and others about bear behavior and coexistence

- Simply leave bears alone

- If you are camping, hiking, or enjoying the outdoors in any way that overlaps bear territory, carry bear spray, talk to park rangers and follow local bear country rules and regulations to ensure a safe and enjoyable outing (westernwildlife.org n.d.).

- For more coexistence tips, visit www.bearsmart.com

As humans encroach further upon bear habitat, the need to understand the importance of bears in our ecosystem becomes ever more critical. Their wellbeing and survival ultimately depends on our tolerance for them around our living spaces. Having a bear management plan focused on non-lethal interventions, involving communities’ leaders in critical decisions that reduce bear conflicts, and creating educational outreach programs that promote desired human behaviors (e.g., removing attractants and proper aversive conditioning) are all ways in which we can promote non-lethal co-existence with one of our most important North American carnivores (Dietsch et al. 2018, ncwildlife.org n.d., Marlet et al. 2017, Northrup et al. 2023, Schwartz et al. 2012).

LITERATURE CITED

American Black Bear. (n.d.). USDA Forest Service. Retrieved February 28, 2023, from https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/npnht/learningcenter/nature-science/?cid=fseprd696195

Bear. (2019). In New World Encyclopedia. https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Bear

Behavior. (n.d.). Bear Smart. Retrieved March 16, 2022, from https://www.bearsmart.com/about-bears/behaviour/

Black Bears. (2022, April 5). National Park Service. Retrieved February 14, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/subjects/bears/black-bears.htm.

Black Bear. (n.d.). Defenders of Wildlife. Retrieved July 22, 2015, from https://defenders.org/wildlife/black-bear

Brown Bear Species Profile, Alaska Department of Fish and Game. (n.d.). Retrieved July 21, 2015, from http://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=brownbear.main

Boulanger, J., Cattet, M., Nielsen, S.E., Stenhouse, G., Cranston, J. (2013). Use of Multistate Models to Explore Relationships Between Changes in Body Condition, Habitat, and Survival of Grizzly Bears Ursus Arctos Horribilis. Wildlife Biology, 19:3

Burt, W. H., & Grossenheider, R. P. (1976). A field guide to the mammals: Field marks of all North American species found north of Mexico (3d ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company.

Black Bear. (n.d.). Defenders of Wildlife. Retrieved February 19, 2022, from https://defenders.org/wildlife/black-bear

Brown Bear. (2023, January 12). New World Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 2, 2023, from https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Brown_bear

Cronin, M.A., McDonough, M.M., Huynh, H.M., Baker, R.J. (2013). Genetic Relationships if North American Bears (Ursus) Inferred from Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphisms and Mitochondrial DNA Sequences. Canadian Journal of Zoology 91: 626-634.

Coexisting with Black Bears. (n.d.). Retrieved July 21, 2015, from http://www.ncwildlife.org/portals/0/Learning/documents/Species/CoexistWithBears.pdf

Dietsch, A. M., Slagle, K. M., Baruch-Mordo, S., Breck, S. W., & Ciarniello, L. M. (2018). Education is not a panacea for reducing human–black bear conflicts. Ecological Modelling, 367, 10–12.

Dispelling myths. (n.d.). Bear Smart. Retrieved March 28, 2022, from https://www.bearsmart.com/about-bears/dispelling-myths/

Dubois, S., Fraser, D. (2013). Local Attitudes towards Bear Management after Illegal Feeding and Problem Bear Activity. Animals 3: 935-950

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2018). Miocene Epoch. In Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/Miocene-Epoch

Food and diet. (n.d.). Bear Smart. Retrieved July 21, 2015, from https://www.bearsmart.com/about-bears/food-diet/

Fricke, C. (2021, July 21). American Black Bear. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/american-black-bear.htm

Grizzly bears. (2014). Retrieved July 21, 2015, from http://www.davidsuzuki.org/issues/wildlife-habitat/science/critical-species/grizzly-bears/

Grizzly Bear. (n.d.). National Geographic. Retrieved July 21, 2015, from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/facts/grizzly-bear

Grizzly Biology & Behavior – Western Wildlife Outreach. (n.d.). Retrieved July 21, 2015, from http://westernwildlife.org/grizzly-bear-outreach-project/biology-behavior/

Hardeman, D. W., Zanden, H. B. Vander, Mccown, J. W., Scheick, B. K., & Mccleery, R. A. (2023). Black Bear Behavior and Movements Are Not Definitive Measures of Anthropogenic Food Use. Animals, 1–14.

Harrer, L. E. F., & Levi, T. (2018). The primacy of bears as seed dispersers in salmon-bearing ecosystems. Ecosphere, 9(1).

Herrero, S. (n.d.) Conflicts Between Man and Grizzly Bears in the National Parks of North America. Third International Conference on Bears. Retrieved 21 July 2015, from http://www.bearbiology.com/fileadmin/tpl/Downloads/URSUS/Vol_3/SHerrero_Vol_3.pdf

Hopkins III, John B. (2013) Use of genetics to investigate socially learned foraging behavior in free-ranging black bears. Journal of Mammalogy (94)6: 1214–1222.

Immell, D., Jackson, D.H., Boulay, M.C. (2014). Home-Range Size and Subadult Dispersal of Black Bears in the Cascade Range of Western Oregon. Western North American Naturalist 74(3): 343-348.

Krause, J., Unger, T., Nocon, A., Malaspinas, A-S., Kolokotonis, S-O., Stiller, M., Soibelzon, L., Spriggs, H., Dear, P.H., Briggs, A.W., Bray, S., O’Brien, S.J., Rabeder, G., Matheus, P., Cooper, A., Slatkin, M., Paabo, S., Hofreiter, M. (2008). Mitochondrial Genomes Reveal An Explosive Radiation of Extinct and Extant Bears near the Miocene-Pliocene Boundary. BMC Evolutionary Biology 8:220

Know the difference. (n.d.). Bear Smart. Retrieved July 21, 2015, from https://www.bearsmart.com/about-bears/know-the-difference/

Lacey Act. (n.d.). Retrieved September 6, 2015, from http://www.fws.gov/international/laws-treaties-agreements/us-conservation-laws/lacey-act.html

Living with Wildlife in the Northern Rockies: Coexisting with Grizzly Bears.(2012, August 29). Retrieved July 17, 2015, from http://www.defenders.org/sites/default/files/publications/coexisting-with-grizzly-bears-in-northern-rockies.pdf

Marley, J., Hyde, A., Salkeld, J.H., Prima, M.-C., Parrott, L., Senger, S.E., Tyson, R.C., 2017. Does human education reduce conflicts between humans and bears?: an agent-based modelling approach. Ecol. Model. 343, 15–24.

Mathews, S.M., Greenleaf, S.S., Leithead, H.M., Beecham, J.J., & Quigley, H.B. (2003). Final Report: Bear Element Assessment Focused on Human-Bear Conflicts in Yosemite National Park. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/yose/learn/nature/upload/bearstudy-bears-reduce.pdf.

Mattson, D. J., & Merrill, T. (2002). Extirpations of Grizzly Bears in the Contiguous United States, 1850 – 2000. Conservation Biology, 16(4), 1123–1136.

Merkle, J.A., Robinson, H.S., Krausman, P.R., Alaback, P. (2013). Food Availability and Foraging Near Human Developments by Black Bears. Journal of Mammalogy, 94(2), 378-385.

Mouquet, N., Gravel, D., Massol, F., Calcagno, V. (2013). Extending the Concept of Keystone Species to Communities and Ecosystems. Ecology Letters, 16, 1-8

North America’s Bears. (n.d.). Bear Smart. Retrieved February 18, 2022, from https://www.bearsmart.com/about-bears/north-americas-bears/

Northrup, J. M., Newton, E., Potter, D., Howe, E., Inglis, J., Pond, B., & Obbard, M. E. (2023). Experimental test of the efficacy of hunting for controlling human – wildlife conflict. October 2022, 1–18.

Nowak, R. M. (1999). Walker’s Mammals of the World (6th ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press.

Rovang, S., Neilsen, S.E., Stenhouse, G. (2014) Detectability of Fixed Hair Trap DNA Methods in Grizzly Bear Population Monitoring. Wildlife Biology 21: 68-79

Sawaya, M.A., Clevenger, A.P., Kalinowski, S.T. (2013). Demographic Connectivity for Ursid Populations at Wildlife Crossing Structures in Banff National Park. Conservation Biology, 27(4), 721-730.

Schwartz, C.C., Gude, P.H., Landenburger, L., Haroldson, M.A., Podruzny, S. (2012). Impacts of Rural Development on Yellowstone Wildlife: Linking Grizzly Bear Ursus arctos Demographics with projected residential Growth. Wildlife Biology, 18(3), 246-257.

Schwartz, C. C., Miller, S. D., & Haroldson, M. A. (2003). Grizzly Bear. In Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Conservation (Issue 2, pp. 556–586).

Spady, T.J., Lindburg, D.G., Durrant, D.S. (2007). Evolution of Reproductive Seasonality in Bears. Mammal Review, 37(1), 21-53.

Stenhouse, G., Boulanger, J., Lee, J., & Graham, K. (2009). Grizzly Bear Associations along the Eastern Slopes of Alberta Grizzly bear associations along the eastern slopes of Alberta. Ursus, 6176(January).

Struzik, E. (2006). Grizzly Bears on Ice. Retrieved July 21, 2015, from https://www.nwf.org/News-and-Magazines/National-Wildlife/Animals/Archives/2006/Grizzly-Bears-on-Ice.aspx

Taylor, J.D. and J.P. Phillips. (2020). Black Bear. Wildlife Damage Management Technical Series. USDA, APHIS, WS National Wildlife Research Center. Fort Collins, Colorado. 30p.

The Ecological Role of Coyotes, Bears, Mountain Lions, and Wolves. (n.d.). Retrieved July 21, 2015, from http://www.predatordefense.org/docs/ecological_role_species.pdf

The Wildlife Team, Denali National Park and Preserve (2003). Bear-Human Conflict Management Plan. Center for Resources Science and Learning

Tips for Coexistence with Black Bears – Western Wildlife Outreach. (n.d.). Retrieved July 21, 2015, from http://westernwildlife.org/black-bear-outreach-project/tips-for-coexistence-with-black-bears/

Trafficking of Bear Parts. (2008). Retrieved July 21, 2015, from http://www.bigwildlife.org/trafficking.php

Unger, D.E., Cox, J.J., Harris, H.B., Larkin, J.L., Augustine, B., Dobey, S., Guthrie, J.M., Hast, J.T., Jensen, R., Murphy, S., Plaxico, J., & Maehr, D.S. (2013). History and Current Status of the Black Bear in Kentucky. Northeastern Naturalist, 20(2): 289-308.

United States National Park Service. (2015, July 20). Denning and Hibernation Behavior. Retrieved July 21, 2015, from http://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/denning.htm

U.S. Bear Gallbladders Sold on Black Market. (2010). Retrieved July 22, 2015, from http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2009/08/090811-bear-parts-trade_2.html

Waits, L. P., Talbot, S. L., Ward, R. H., & Shields, G. F. (1998). Mitochondrial DNA Phylogeography of the North American Brown Bear and Implications for Conservation. Conservation Biology, 12(2), 408–417.

What are Keystone Species? (n.d.). Retrieved July 21, 2015, from http://www.keystoneconservation.us/keystone_conservation/keystone-species.html

Willson, M. F. 1993. Mammals as seed-dispersal mutu- alists in North-America. Oikos 67:159–176.

Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). Carnivora. In Wilson, D.E., & Reeder D.M. (eds.), Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed., pp. 532-628). The John Hopkins University Press.

Young, S., Jackson, H. (1978). The Clever Coyote. University of Nebraska Press