Coyotes

WHY COYOTES

Coyotes, our unique Song Dogs who have existed in North America since the Pleistocene, are the most persecuted wild carnivore in North America. The coyote is the flagship species for all misunderstood and exploited wild carnivores. Poisoned, trapped, aerial gunned and killed for bounties and in contests, over half a million coyotes are slaughtered every year in the U.S.

Maligning stereotypes and fallacies follow coyotes wherever they go. Unlike many predators who face extinction, coyotes continue to survive and thrive in the face of persecution. Their survival is attributed to their intelligence, adaptability, and resilience, traits many Native Americans revered in the coyote as the trickster.

A vital part of both our rural and urban landscapes, coyotes’ ability to adjust to changing conditions and diverse environments sets them apart and makes them difficult to pigeonhole, perhaps further contributing to people’s fear and misunderstanding.

In their intelligence and adaptability, coyotes teach us about our own capacity to evolve and coexist in the face of rapid ecological and social change. By helping to shift attitudes toward coyotes and other native carnivores, we replace fear and ignorance with understanding and appreciation.

As the only organization whose mission is to foster coexistence between people and carnivores and compassionate conservation through education, science and advocacy, Project Coyote builds a critical bridge between wildlife conservation and animal wellbeing, bringing the best science and ethics to our advocacy on behalf of coyotes and other native carnivores.

The United States Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services accounts for over 64,000 of the hundreds of thousands of coyotes who are killed each year. As shown below, most are killed for so-called recreation. Many states allow unlimited killing of coyotes including the following practices:

- Bounties (starting at as little as $1 for each animal killed)

- Poisoning (using Compound 1080 and Sodium Cyanide M-44s)

- Aerial gunning (shooting animals from low-flying aircraft on private and public lands)

- Leghold trapping (which are nonselective and often injure non-target species)

- Snaring (a lethal wire intended to catch and strangle a coyote to death- also nonselective and often injure non-target species)

- Calling & shooting (distress calls of wounded young or prey are used to lure coyotes in to point blank range where they are shot)

- Hound hunting (pursued by hounds and torn apart)

- Killing contests, derbies or tournaments (where awards are given for macabre achievements such as killing the most or largest animals)

- Denning (the killing of coyote pups in their dens)

ECOLOGY OF COYOTES

Evolution

Coyotes (Canis latrans) come from an older lineage of Canis than the gray wolf, as shown by their relatively small size and their comparatively narrow skull and jaws, which lack the grasping power necessary to hold the large prey wolves specialize in. They are not as specialized a carnivore as the wolf is, as shown by the larger chewing surfaces on the molars, reflecting the species’ relative dependence on vegetable matter. In these respects, the coyote resembles the fox-like progenitors of the genus more so than the wolf (Nowak, 1978). The evolution of coyotes can be traced back to an extinct type of small omnivorous fox-like canid endemic to North America 10.3—3.6 million years ago (Kurten, 1980).

Modern coyotes arose during the Middle Pleistocene, and showed much more variation than they do today (Nowak, 1978). They were larger and more robust, likely in response to larger competitors and prey (Meachen and Samuels, 2012).

Their reduction in size occurred after an extinction event, when their larger prey died (Meachen and Samuels, 2012).

Furthermore, Pleistocene coyotes were unable to exploit the big game hunting niche left vacant after the extinction of the dire wolf, as it was rapidly filled by gray wolves, which likely actively killed off the large coyotes (Meachen et al, 2014). Instead, they evolved to be the highly adaptable species they are today, hunting mostly rabbits and rodents but able to hunt larger prey when available.

Distribution

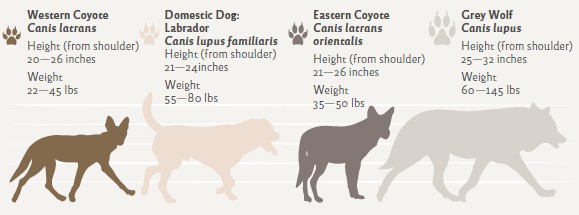

A map of the distribution of the 19 known subspecies of canis latrans plus Canis latrans “var”, the Eastern Coyote, a hybrid between the coyote and wolf.

- Canis latrans cagottis

- Canis latrans clepticus

- Canis latrans dickeyi

- Canis latrans frustor

- Canis latrans goldmani

- Canis latran hondurensis

- Canis latrans impavidus

- Canis latrans incolatus

- Canis latrans jamesi

- Canis latrans latrans

- Canis latrans lestes

- Canis latrans mearnsi

- Canis latrans microdon

- Canis latrans ochropus

- Canis latrans peninsulae

- Canis latrans texensis

- Canis latrans thamnos

- Canis latrans umpquensis

- Canis latrans vigilis

- Canis latrans “var”

Social Structure

Coyotes may live as solitary individuals, in pairs, or in small family groups, both in rural and urban areas. Coyotes are generally monogamous, with pair bonds frequently lasting many years, and some for life. Urban coyotes are especially known for high rates of monogamy, showing 100% dedication to their mates in some areas (Hennessy et al. 2012). Both male and female coyotes actively maintain territories that may vary in size from two to 30 square miles.

Reproduction is once per year and typically limited to the family’s parents. Breeding season peaks in mid February, followed by three to seven (3-7) pups born in a den from March to May (Carlson & Gese 2008). Pup mortality is high, with an average of 50-70% dying within their first year. Some juveniles disperse in late fall to seek new territory, and some individuals remain with their parents/family group.

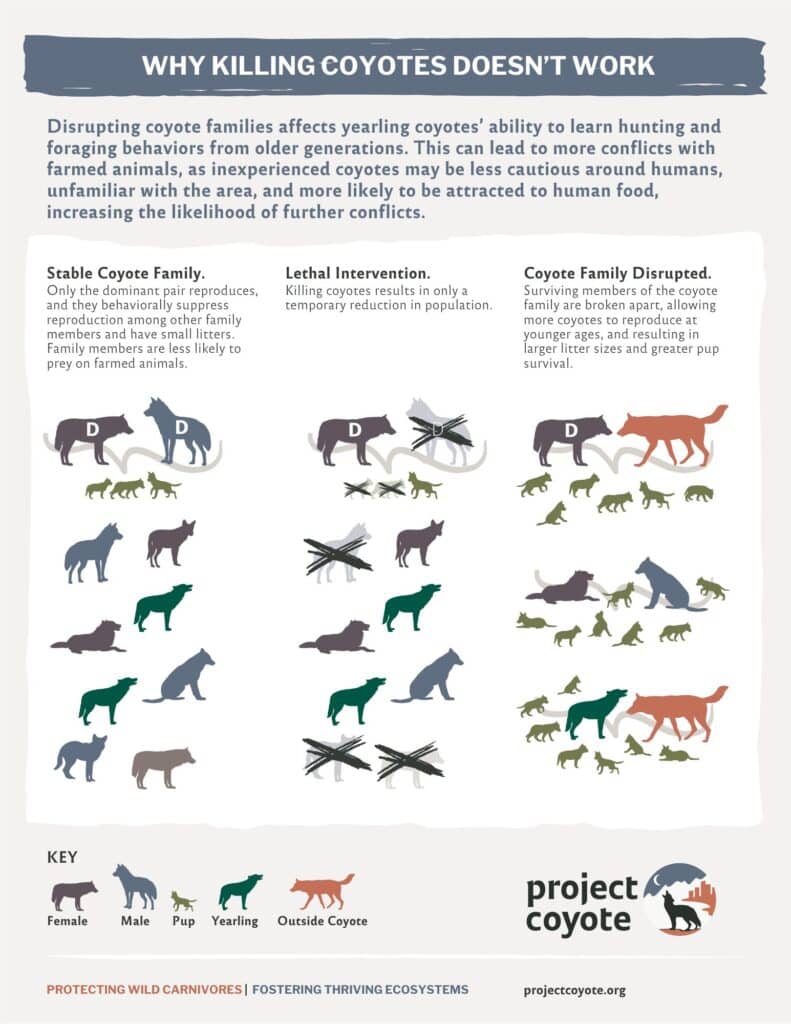

The graphic below produced by the Humane Society of the United States illustrates how predator management programs focused on killing coyotes disrupt the pack structure.

Appearance

Behavior

Coyotes are highly intelligent and social animals; they learn quickly and are devoted parents. Their intelligence and sociability are integral to their wellbeing and adaptability, and through those physiological traits, to their ecology and evolution. Coyotes’ adaptability allows them to interact in a variety of ways and contexts with humans, sometimes in ways that evoke human concern and lethal retaliation (Alexander & Draper, 2019). Yet such traits have allowed coyote populations to not only survive, but thrive and expand despite consistent past attempts at extermination and current ongoing persecution.

In rural habitats, coyotes hunt by day and night. In urban areas, coyotes appear to be more nocturnal but can often be seen during daylight hours, especially at dawn and dusk.

They communicate by vocalizing, scent marking, and through a variety of body displays. It is common to hear them howling and yipping at night, or even during the day in response to sirens and other loud noises. Indeed, coyotes’ scientific name is Canis latrans which means “barking dog.” With approximately a dozen different vocalizations, it is common to mistake a few coyotes communicating with each other for a large group due to their deployment of the ‘beau geste effect’, by which coyotes create the auditory illusion of being more numerous through the use of a variety of sounds and pitches.

Coyotes are fast and agile; they can run at speeds of 25-40 mph (65 km/h) and jump six feet.

Coyotes and Dogs

Coyotes and dogs are related and as such, can exhibit similar behaviors. However, curiosity and play are often misinterpreted as boldness or aggressiveness. Coyotes usually communicate using a wider range of vocalizations than dogs. In the presence of other canids and humans, coyotes generally vocalize to signal their presence and keep intruders away, without such vocalizations signaling intent to engage with intruders.

Diet

MANAGEMENT

Coyotes and Humans

When coyotes live close to human populations, conflicts — often driven by fears of predation on domesticated animals — may arise, and most conflicts continue to result in de-facto killing of coyotes (Fox and Papouchis, 2005; Fox, 2006). However, despite decades of poisoning, trapping, and shooting, coyotes persist in North America today and conflicts with people continue. Two hundred years of costly persecution have not eliminated the resilient coyote, but raise significant animal wellbeing issues (Alexander, 2015).

Claims that coyotes threaten humans and domesticated animals are greatly exaggerated. A study of coyote attacks on humans over a 38-year period (1977-2015) found only 367 documented attacks by non-rabid coyotes in Canada and the U.S., two of which resulted in death (Baker & Timm, 2017). In comparison, there are more than 4.5 million dog bites annually in the U.S., approximately 800,000 of which require medical attention (AMVA).

Most coyotes do not prey on domesticated animals (Sacks et al. 1999a 1999b). Studies show the presence of companion animals in coyote scat to be minimal (<2%, Lukasik & Alexander, 2011; Poessel et al. 2017a). U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) data shows domesticated cows and sheep losses to carnivores to also be minimal. In 2015, less than 0.30% of the U.S. cows and sheep inventories (including calves and lambs) were lost to all carnivores combined—including coyotes, wolves, cougars, bears, vultures, dogs, and unknown carnivores. The predominant sources of mortality to cows and sheep, by far, are non-predator causes including disease, illness, birthing problems, and weather (USDA 2015a,b).

Why is killing ineffective and ecologically disruptive? Coyotes’ remarkable success appears to be closely related to human attempts to control their numbers. Unexploited coyote populations are self-regulating based on the availability of food, habitat, and territorial defense by resident family groups. Typically, only the parents (the ‘dominant pair’) in a family of coyotes reproduce, and they behaviorally suppress reproduction among subordinate members of the group (Gese 2005, Knowlton 1972, Knowlton et al 1999, Sacks 2005). Lethal control can disrupt coyote families, breaking them up, allowing more coyotes to reproduce, encouraging larger litter sizes because of decreased competition for food and habitat, and increasing pup survival rates (Goodrich and Buskirk 1995; Crabtree & Sheldon 1999; Kilgo et al. 2017, Knowlton et al. 1999). More critically, with the disruption of pack structure, learning across generations of coyotes that promotes consumption of wild prey can be compromised and increase killing of domesticated animals (Crabtree and Sheldon 1999; Mitchel et al, 2004). Additionally, the void created by removing coyotes who are not causing conflicts may be filled by other coyotes who may be less wary of humans and cause conflicts (Conner et al. 1998, Fox 2006, Gehrt 2004, Sacks 1999b, Shivik 2014).

Despite the ineffectiveness and destructiveness of lethal approaches, hundreds of thousands of coyotes are killed every year in the U.S by federal, state and local governments as well as private individuals (Fox and Papouchis 2005). Most of this killing is carried out in the name of “livestock protection” at the behest of agribusiness and private ranchers. U.S taxpayers subsidize this predator carnage at the cost of 100 million dollars annually. (Read more about the USDA’s Wildlife Services program here.) Indiscriminate lethal control in the name of “management” persists, despite scientific evidence that this approach has significant negative ecological and wellbeing implications and is ultimately economically ineffective (Fox 2006).

Coyotes are also killed for their fur, for “sport,” for fun, for hate, and in wildlife killing contests where prizes are awarded for gruesome achievements like killing the most, smallest, or largest coyotes. Most states set no limit on the number of coyotes who may be killed, nor do they regulate the killing methods. While killing coyotes en masse or relocating individual coyotes can reduce their population in the very short term, it is not recommended for clear and important reasons described above.

Project Coyote implements a number of programs that demonstrate how to peacefully coexist with coyotes and other wildlife in both urban and rural communities. You can download coexistence information here about coexisting with coyotes, including tips for keeping dogs and domesticated cows and sheep safe.

ECOLOGICAL ROLE

Adaptable to diverse environments, coyotes provide the following ecological benefits:

Coyotes limit mesocarnivore populations and increase bird diversity and abundance (Avrin et al. 2023, Crooks and Soule 1999, Gehrt et al. 2013, Henke & Bryant 1999, Kays et al. 2015). Studies indicate that coyotes limit mesocarnivore (foxes, feral cats, raccoons, skunks) populations largely through competitive exclusion, thereby having a positive impact on ground-nesting birds and songbird diversity and abundance.

Coyotes keep rodent and rabbit populations in check. Rodents and lagomorphs (rabbits and hares) are important food items for coyotes, often making up more than half of the dry weight of prey items found in scats (Fedriani et al. 2001; Morey et al. 2007). However, this percentage varies regionally, seasonally, and by level of urbanization – all of which affect the availability of rodents and lagomorphs as prey items. Laundré and Hernandez (2003) estimated 162 – 192 lagomorphs or 3110 – 3681 rodents per year are needed to fulfill metabolic needs (more if breeding/lactation was accounted for) for coyotes in the Great Basin Desert – and that therefore lagomorphs were a better energy return on hunting investment.

Thus, coyotes provide benefits to both urban and rural communities by keeping rodent and lagomorph populations in check. City dwellers enjoy cleaner environments (and avoid having to use rat poisons that can impact non-target animals). Ranchers benefit from coyotes controlling micro-herbivores (such as rabbits and gophers) that otherwise compete with their grazing animals for food. Farmers also suffer less crop loss or damage when coyotes naturally control rodent populations.

Coyotes help control disease transmission. Coyotes provide an invaluable public health service by helping to control rodents, thus reducing the spread of rodent-borne zoonotic diseases such as plague and hantavirus (Watts et al. 2014).

Coyotes clean up the environment. As scavengers, coyotes provide an ecological service by helping to keep our communities clean of carrion (dead things).

TIPS AND TOOLS FOR COEXISTENCE

Prevention—not lethal control—is the best method for minimizing conflicts with coyotes in urban and rural settings. Many studies provide evidence that practicing good animal husbandry and using strategic, nonlethal predator control methods to protect domesticated animals (such as electric fences, sound-visual deterrents, guard animals), removing attractants (like carcasses and pet food) and aversive conditioning (‘hazing’) are more effective than lethal control at preventing conflicts (Baker et al. 2008, Treves et al. 2011, Treves et al. 2016, Treves & Karanth 2003, Sampson & Van Patter 2020, Shivik et al. 2003, Shivik 2014, VerCauteren et al. 2003).

Urban and rural residential landscapes offer an abundance of food, water, and shelter for coyotes. In these environments, a combination of providing coyotes with adequate habitat (including green areas with shelter, water and wild prey) and removing attractants from residences may decrease conflicts with humans and domesticated animals (Poessel et al. 2017b). Take the following steps to prevent coyotes from being attracted to your home:

- Wildlife-proof garbage in sturdy containers with tight fitting lids.

- Don’t leave pet food outside.

- Take out trash the same morning pick up is scheduled.

- Keep compost in secure containers.

- Keep fallen fruit off the ground. Coyotes eat fruit.

- Keep birdseed off the ground; seeds attract rodents which then attract coyotes. Remove feeders if coyotes are seen in your yard.

- Keep barbecue grills clean.

Eliminate accessible water sources. - Clear away brush and dense weeds near buildings. This action will also increase your home’s defensible space if you live in an area where wildfires can occur.

- Close off crawl spaces under decks and around buildings where coyotes may den.

- If you frequently see a coyote in your yard, make loud noises with pots, pans, or air horns, and haze the coyote with a water hose.

- Share this list with your neighbors; coexistence is a neighborhood effort.

Discover additional coyote coexistence methods here.

LITERATURE CITED

Alexander, S.M. 2015. “Carnivore conflict, management, and conservation GIS in Canada.” In B. Mitchell, ed., Resources and Environmental Management in Canada. Ontario: Oxford University Press, 293-317.

Alexander, S. M., & Draper, D. L. 2019. The rules we make that coyotes break. Contemporary Social Science, 16(1), 127–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/21582041.2019.1616108

Alexander, S.M. and M.S. Quinn. 2011.” Coyote (Canis latrans) interactions with humans and pets reported in the Canadian print media (1995–2010).” Human Dimensions of Wildlife 16:345-359.

Allen, JJ, M. Bekoff, and RL Crabtree. 1999. An observational study of coyote (Canis latrans) scent-marking and territoriality in Yellowstone National Park. Ethology 105:289-302.

Atkinson, K.T., and D.M. Shackleton. 1991. Coyote, Canis latrans, ecology in a rural-urban environment. Canadian Field-Naturalist 105:49-54.

Avrin, A. C., Sperry, J. H., Pekins, C. E., Wilmers, C. C., & Allen, M. L. (2023). Can a mesocarnivore fill the functional role of an apex predator ? Ecosphere, September 2022, 1–17.

Baker, P. J., Boitani, L., Harris, S., Saunders, G., & White, P. C. L. 2008. Terrestrial carnivores and human food production: Impact and management. Mammal Review, 38(2–3), 123–166.

Baker, R. O., & Timm, R. M. 2017. Coyote attacks on humans, 1970–2015: Implications for Reducing the Risks. Human-Wildlife Interactions, 11(2), 1970–2015.

Berger, K. (2006) Carnivore-livestock conflicts: Effects of subsidized predator control and economic correlates on the sheep industry. Conservation Biology, 20(3), 751 – 761.

Bekoff, Marc. 1978. Coyotes: Biology, Behavior, and Management. Academic Press, Inc., New York, New York.

Bekoff, Marc. 1995. Coyotes: Victims of their own Success. Canid News 3:1-6.

Bekoff, M., and Wells, M.C. 1986. Social ecology and behavior of coyotes. Adv. Study Behav. 16: 251–338.

Bishop, C. J., White, G. C., Freddy, D. J., Watkins, B. E., & Stephenson, T. R. 2009. Effect of Enhanced Nutrition on Mule Deer Population Rate of Change. Wildlife Monographs, 172, 1–28.

Bragina, E. V., Kays, R., Hody, A., Moorman, C. E., DePerno, C. S., & Mills, S. L. 2019. Effects on White-Tailed Deer Following Eastern Coyote Colonization. Journal of Wildlife Management, 1–9.

Carlson, D. A., & Gese, E. M. (2008). Reproductive biology of the coyote (Canis latrans): Integration of mating behavior, reproductive hormones, and vaginal cytology. Journal of Mammalogy, 89(3), 654–664.

Conner, M. M., Jaeger, M. M., Weller, T. J., & McCullough, D. R. 1998. Effect of coyote removal on sheep depredation in northern California. Journal of Wildlife Management, 62, 690–699.

Connolly, G. E. 1995. The effects of control on coyote populations: another look. Symposium Proceedings- Coyotes in the Southwest: A Compendium of Our Knowledge, 23–29.

Connolly, G. E., and W. M. Longhurst. 1975. The effects of control on coyote populations: A simulation model. Division Agricultural Science, University of California, Davis, Bulletin 1872.

Crabtree, RL, and JW Sheldon. 1999. The Ecological Role of Coyotes on Yellowstone’s Northern Range. Yellowstone Science 7(2):15-23.

Crooks KR, Soulé ME. 1999. Mesopredator release and avifaunal extinctions in a fragmented system. Nature 400: 563–566.

Fedriani, J. M., Fuller, T. K., Sauvajot, R. M. 2001. “Does Anthropogenic Food Enhance Densities of Omnivorous Mammals? An Example with Coyotes in Southern California”. Ecography. 24(3): 325-331.

Forrester, T. D., & Wittmer, H. U. 2013. A review of the population dynamics of mule deer and black-tailed deer Odocoileus hemionus in North America. Mammal Review, 43(4), 292–308.

Fox, C. H. 2006. Coyotes and humans: can we coexist? Pp. 287-293 in: R.M. Timm and J. H. O’Brien (eds.), Proceedings, 22nd Vertebrate Pest Conference. Publ. Univ. Calif.-Davis.

Fox, C.H. and C.M. Papouchis. 2005. Coyotes in Our Midst: Coexisting with an Adaptable and Resilient Carnivore. Animal Protection Institute, Sacramento, California.

Gese, Eric M. 2005. Demographic and Spatial Responses of Coyotes to Changes in Food and Exploitation. Proceedings of the Wildlife Damage Management Conference 11: 271–85.

Gese, E. M., Rongstad, O. J., Mytton, W. R. 1988. “Home Range and Habitat Use of Coyotes in Southeastern Colorado”. Journal of Wildlife Management. 52(4): 640-646.

Gehrt, S.D. 2004. Chicago coyotes part II. Wildlife Control Technology. 11(4): 20-21, 38-39, 42.

Gehrt, S.D. and Riley, S.P.D. 2010. Coyotes (Canis latrans). In: Urban Carnivores (Gehrt, S.D., Riley, S.P.D., Cypher, B.L., eds.). John Hopkins University Press. pp. 78-95.

Gehrt SD, Wilson EC, Brown JL, Anchor C. 2013. Population Ecology of Free-Roaming Cats and Interference Competition by Coyotes in Urban Parks. PLOS ONE 8(9): e75718.

Gibeau, M.L. 1998. Use of urban habitats by coyotes in the vicinity of Banff Alberta. Urban Ecosystems 2:129-139.

Henke, S.E. and Bryant, F.C. 1999. Effects of Coyote Removal on the Faunal Community in Western Texas. Journal of Wildlife Management, 63, 1066-1081.

Hennessy, C. A., Dubach, J., & Gehrt, S. D. (2012). Long-term pair bonding and genetic evidence for monogamy among urban coyotes (Canis latrans). Journal of Mammalogy, 93(3), 732–742.

Hody, J. W., & Kays, R. 2018. Mapping the expansion of coyotes (Canis latrans) across North and Central America. 97, 81–97.

Hurley, M. A., Unsworth, J. W., Zager, P., Hebblewhite, M., Garton, E. O., Montgomery, D. M., Skalski, J. R., & Maycock, C. L. 2011. Demographic response of mule deer to experimental reduction of coyotes and mountain lions in southeastern idaho. Wildlife Monographs, 178, 1–33.

Kays, R., Costello, R., Forrester, T., Baker, M. C., Parsons, A. W., Kalies, L., Hess, G., Millspaugh, J. J., & Mcshea, W. 2015. Cats are rare where coyotes roam. Journal of Mammalogy, 96(5), 981–987.

Kilgo, John C., Christopher E. Shaw, Mark Vukovich, Michael J. Conroy, and Charles Ruth. 2017. “Reproductive Characteristics of a Coyote Population before and during Exploitation.” Journal of Wildlife Management 81 (8): 1386–93.

Kitchen, A. M., Gese, E. M., & Schauster, E. R. 1999. Resource partitioning between coyotes and swift foxes: Space, time, and diet. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 77(10), 1645–1656.

Knowlton, F. F. 1972. Preliminary Interpretations of Coyote Population Mechanics with Some Management Implications. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 36(2), 369.

Knowlton, F. F., Gese, E. M., & Jaeger, M. M. 1999. Coyote depredation control: An interface between biology and management. Journal of Range Management, 52(5), 398–412.

Kurtén, Björn.1980. Pleistocene Mammals of North America. pp. 167–9. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231037333.

Laundré, J.W., Hernandez, L. 2003. “Total energy budget and prey requirements of free-ranging coyotes in the Great Basin desert of the western United States”. Journal of Arid Environments. 55(4): 675 – 689

Lukasik, V.M. and S.M. Alexander. 2012. “Spatial and temporal variation of coyote (Canis latrans) diet in Calgary, Alberta.” Cities and the Environment (CATE). Special Topic Issue: Urban Predators 4(11): Article 8. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/cate/vol4/iss1/8/

Meachen, J. A.; Samuels, J. X. (2012). “Evolution in coyotes (Canis latrans) in response to the megafaunal extinctions”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (11): 4191. doi:10.1073/pnas.1113788109. PMID 22371581.

Mitchell, B. R., Jaeger, M. M., Barrett, R. H., 2004. “Coyote Depredation Management: Current Methods and Research Needs”. Wildlife Society Bulletin. 32(4): 1209-1218.

Monteith, K. L., Bleich, V. C., Stephenson, T. R., Pierce, B. M., Conner, M. M., Kie, J. G., & Bowyer, R. T. 2014. Life-history characteristics of mule deer: Effects of nutrition in a variable environment. Wildlife Monographs, 186, 1–62.

Monzon, J., Kays, R., Dykhuizen, D. E. 2014. “Assessment of Coyote-Wolf-Dog Admixture Using Ancestry-Informative Diagnostic SNPs”. Molecular Ecology. 23: 182-197.

Morey, P. S., Gese, E. M., Gehrt, S. 2007. “Spatial and Temporal Variation in the Diet of Coyotes in the Chicago Metropolitan Area”. The American Midland Naturalist. 158(1): 147-161.

Nowak, R. M. (1978) “Evolution and taxonomy of coyotes and related Canis”, pp. 3–16 in M. Bekoff (ed.) Coyotes: Biology, Behavior, and Management. Academic Press, New York.

Patterson, B. R., Messier, F. 2001. “Social Organization and Space use of Coyotes in Eastern Canada Relative to Prey Distribution and Abundance”. Journal of Mammalogy. 82(2): 463-477.

Poessel, S. A., Mock, E. C., & Breck, S. W. 2017a. Coyote (Canis latrans) diet in an urban environment: Variation relative to pet conflicts, housing density, and season. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 95(4), 287–297.

Poessel, S. A., Gese, E. M., & Young, J. K. 2017b. Environmental factors influencing the occurrence of coyotes and conflicts in urban areas. Landscape and Urban Planning, 157, 259–269.

Pryah, D. 1984. “Social Distribution and Population Estimates of Coyotes in North-Central Montana”. The Journal of Wildlife Management. 48(3): 679-690

Riley, S.P.D., R.M. Sauvajot, T.K. Fuller, E.C. York, D.E. Kamradt, C. Bromley, and R.K. Wayne. 2003. Effects of urbanization and habitat fragmentation on bobcats and coyotes in southern California. Conservation Biology 17:566-576.

Rutledge, L. Y., White, B. N., Row, J. R., & Patterson, B. R. (2012). Intense harvesting of eastern wolves facilitated hybridization with coyotes. Ecology and Evolution, 2(1), 19–33.

Sacks, B. N. 2005. Reproduction and body condition of California coyotes (Canis latrans). Journal of Mammalogy, 86(5), 1036–1041.

Sacks B.N., Blejwas K.M., Jaeger M.M. 1999a. Relative vulnerability of coyotes to removal methods on a northern California ranch. J Wildl Manage 63, 939-949; Sacks, B. N., M. M.

Sacks, B. N., Jaeger, M. M., Neale, J. C. C., & McCullough, D. R. 1999b. Territoriality and Breeding Status of Coyotes Relative to Sheep Predation. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 63(2), 593–605.

Sampson, L., & van Patter, L. 2020. Advancing best practices for aversion conditioning (humane hazing) to mitigate human–coyote conflicts in urban areas. Human-Wildlife Interactions, 14(2), 166–183.

Shivik, J. 2014. The Predator Paradox: Ending the War with Wolves, Bears, Cougars, and Coyotes. Beacon Press.

Shivik, J. A., Treves, A., & Callahan, P. 2003. Nonlethal Techniques for Managing Predation: Primary and Secondary Repellents. Conservation Biology, 17, 1531–1537.

Tigas, L.A., D.H. Van Vuren, and R.M. Sauvajot. 2002. Behavioral responses of bobcats and coyotes to habitat fragmentation and corridors in an urban environment. Biological Conservation 108:299-306.

Treves, A., & Karanth, K. U. 2003. Human‐carnivore conflict and perspectives on carnivore management worldwide. Conservation Biology, 17(6), 1491–1499.

Treves, A., Martin, K. A., Wydeven, A. P., & Wiedenhoeft, J. E. 2011. Forecasting Environmental Hazards and the Application of Risk Maps to Predator Attacks on Livestock. Bioscience, 61(6), 451–458.

Treves, A., Krofel, M., & McManus, J. 2016. Predator control should not be a shot in the dark. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14(7), 380–388.

USDA. 2015a. “Cattle and Calves Death Loss in the United States Due to Predator and Nonpredator Causes, 2015.” USDA–APHIS–VS–CEAH, available at: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/general/downloads/cattle_calves_deathloss_2015.pdf

USDA. 2015b. “Sheep and Lamb Predator and Nonpredator Death Loss in the United States, 2015.” USDA–APHIS–VS–CEAHNAHMS, available at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/nahms/sheep/downloads/sheepdeath/SheepDeathLoss2015.pdf.

VerCauteren, K. C., Lavelle, M. J., & Moyles, S. 2003. Coyote-activated frightening devices for reducing sheep predation on open range. USDA National Wildlife Research Center-Staff Publications, 285.

Wang, X., R.H. Tedford, and M. Anton. 2010. Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. Columbia University Press. 219pp.

Ward, J. N., Hinton, J. W., Johannsen, K. L., Karlin, M. L., Miller, K. V., & Chamberlain, M. J. 2018. Home range size, vegetation density, and season influences prey use by coyotes (Canis latrans). PLoS ONE, 13(10), 1–22.

Watts, A., V.M. Lukasik, S.M. Alexander, and M.J. Fortin. 2015. “Urbanization, grassland, and diet influence coyote (Canis latrans) parasitism structure.” EcoHealth DOI: 10.1007/s10393-015-1040-5

Way, J.G. 2003. Description and possible reasons for an abnormally large group size of adult eastern coyotes observed during summer. Northeastern Naturalist 10(3): 335-342.

Way, J.G. 2007. Social and Play Behavior in a Wild Eastern Coyote (Canis latrans var.) pack. Canadian Field-Naturalist 121(4): 397-401.

Way, J.G. 2013. Taxonomic Implications of Morphological and Genetic Differences in Northeastern Coyotes (Coywolves) (Canis latrans × C. lycaon), Western Coyotes (C. latrans), and Eastern Wolves (C. lycaon or C. lupus lycaon). Canadian Field-Naturalist 127(1): 1–16.

Way, J.G. and Lynn, W.S. 2016. Northeastern coyote/coywolf taxonomy and admixture: A meta-analysis. Canid Biology & Conservation 19(1): 1-8. Retrieved from http://www.canids.org/CBC/19/northeastern_coyote_taxonomy.pdf.

White, L. A., & Gehrt, S. D. 2009. Coyote attacks on humans in the United States and Canada. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 14(6), 419–432.

Young, J. K., Hammill, E., & Breck, S. W. 2019. Interactions with humans shape coyote responses to hazing. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1–9.