American Foxes

ECOLOGY OF FOXES

Evolution

Foxes are omnivorous mammals found in the order Carnivora and, within Carnivora, found in the family known as Canidae, also known as the dog family (“Fox” 2023). Numerous fox species exist across the globe, with about 27 currently extant species (“Fox” 2023).

Around ten or so fox species are considered “true foxes” because they fall into the genus Vulpes (“Fox” 2023). “True foxes” that are found in North America include the red fox (Vulpes vulpes), swift fox (Vulpes velox), and kit fox (Vulpes macrotis) (“Fox” 2023, “Vulpes macrotis Merriam 1888” n.d. “Vulpes velox (Say 1823)” n.d.). The swift fox and kit fox are closely related to each other, having shared the Great Plains of the U.S. and Canada at a point in time (Marks 2006).The red fox is more widely distributed and includes 45 subspecies (Vulpes vulpes) (“Vulpes vulpes (Linnaeus, 1758)”). In both North America and the Old World, fox fossils from the genus Vulpes indicate this genus has been around since the late Miocene (Lucenti and Madurell-Malapeira 2020). However, the North American species Vulpes stenognathus and Vulpes kernensis represent the two oldest records of Vulpes (Lucenti and Madurell-Malapeira 2020).

Another North American fox species is the gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus). The gray fox is not considered a “true fox” since this species is not part of the genus Vulpes but instead is part of the genus Urocyon (“Fox” 2023, “Urocyon cinereoargenteus (Schreber 1775)” n.d.). Sixteen subspecies of the gray fox are spread throughout North America (“Urocyon cinereoargenteus (Schreber 1775)” n.d.). Gray foxes have been around since the Pleistocene era, making them the most basal canid species still alive today. They have a special evolutionary adaptation to climb trees thanks to an extra bone in their wrists, making them one of only 3 canid species that can climb trees (gray foxes, island fox, and asian racoon dog).

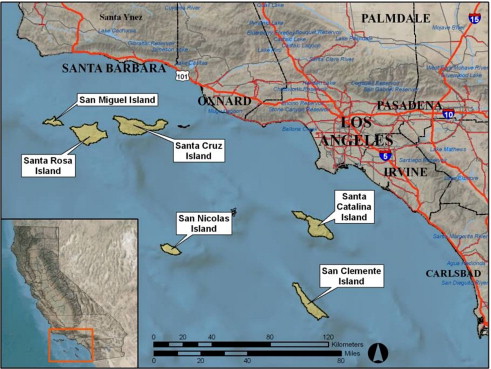

The gray fox is closely related to another North American fox, the island fox (Urocyon littoralis) (“Fox” 2023, Hofman et al. 2015, “Urocyon Baird 1857″ n.d.). The island fox is a descendant of the gray fox and the only other living member of the genus Urocyon (“Island Fox” 2021, “Urocyon Baird 1857″ n.d.). A study in 2015 found island foxes are more closely related to northern California gray foxes that probably experienced a southward range shift due to climate (Hofman et al. 2015). They are found on six California Channel Islands, and each island population is considered a unique subspecies of the island fox (“Island Fox” 2021).

Distribution

Red Fox Distribution

Gray Fox Distribution

Island Fox Distribution

The island fox is endemic to six of the eight Channel Islands that lay off southern California’s coast; Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, San Miguel, San Nicolas, San Clemente, and Santa Catalina islands (“Island Fox” 2021). Island foxes arrived on Santa Catalina, San Nicolas, and San Clemente through the Chumash native people (“Island Fox” 2021). However, how foxes arrived on the other Channel Islands is still not completely understood. One hypothesis is that the water was low enough 10,000 to 20,000 years ago that foxes could “raft” across on debris to a large island known at the time as Santarosae, now known as the islands Santa Cruz, San Miguel, Anacapa, and Santa Rosa (“Island Fox” 2021). Although, the foxes wouldn’t have survived on Anacapa due to the scarcity of freshwater (“Island Fox” 2021). Another hypothesis comes from more recent archeological findings dating the oldest island fox fossil to 6,000 years ago, which was after humans had arrived on the islands; thus, gray foxes could have arrived via humans and then evolved (“Island Fox” 2021).

Swift Fox Distribution

Kit Fox Distribution

Habitat

Red Fox Habitat

Gray Fox Habitat

Island Fox Habitat

Swift Fox Habitat

Kit Fox Habitat

Social Structure

Red Fox Social Structure

Red foxes are monogamous. The breeding season for red foxes starts in December and lasts through April, with most breeding occurring in January and February (“Red Fox” n.d.b). Females give birth after 52 days to litters as small as one kit to as large as twelve kits, with an average of three to six kits (“Red Fox” n.d.b). Both females and males care for the kits (“Red Fox” n.d.b). Dispersal is male biased (Harris & Trewhela 1988). Male dispersal seems driven by inbreeding avoidance, while female dispersal seems influenced by the fitness advantages associated with cohabiting with the same-sex dominant parent, i.e. dispersing females were more likely to have subordinate, rather than dominant, mothers (Whiteside et al. 2011). Territoriality is maintained throughout the year (“Red Fox” n.d.b).

Red foxes have a versatile social system (Dorning & Harris 2019). One study in an urban area of Bristol, United Kingdom found that red foxes formed communities based on shared territorial space, and fox communities consisted of a dominant pair and many subordinates (Dorning & Harris 2019). Furthermore, the study found that some foxes maintained long-term relationships with each other until death or dispersal, with long-term relationships often between foxes who shared territory (Dorning & Harris 2019). On the other hand, short-term relationships, or those that only lasted a day, were found to be between foxes in other territories or foxes that were dispersing, respectively (Dorning & Harris 2019). The length of the relationship seemed to vary seasonally, demonstrating that relationships, specifically between red foxes that don’t share territory, are likely influenced by their yearly life cycles (Dorning & Harris 2019). Additionally, reconnections between foxes were found to be the highest when kits are being raised, around spring and summer (Dorning & Harris 2019). Lastly, red foxes were also observed to have preferred companions as well as individuals they avoid (Dorning & Harris 2019), further demonstrating a complex social structure.

Gray Fox Social Structure

Gray foxes are typically solitary except during the times when they mate and care for young (Vu 2011). However, according to Saunders’ Adirondack Mammals, despite being mostly solitary, they may also maintain pair bonds that are permanent (as cited in “Gray Fox” n.d.b). They are usually monogamous but can be polygamous or polyandrous (Vu, 2011). The male-female pairings begin in the fall, with breeding in winter from January to March, but as early as December in places like Texas (Vu 2011). Kits are usually born after 53 to 63 days (Vu 2011). From September to October, attracting mates is competitive, and males are more aggressive in defending mates (Vu 2011). Both parents care for offspring, with males doing more hunting before birth while females find and prepare a den (Vu 2011). Weaning of the kits begins at two to three weeks old when kits eat food provided mainly by their father (Vu 2011). Pups depend on parents to defend them up until ten months old, when they are sexually mature and may disperse (Vu 2011).

According to Saunders’ Adirondack Mammals, in social encounters, gray foxes may use visual, chemical, tactile, or vocal signals (as cited in “Gray Fox” n.d.b). Additionally, gray foxes are noted to chuckle, growl, and squeal, and during breeding season, sharply bark or yip (Saunders, as cited in “Gray Fox” n.d.b). Adults will use scent glands to mark food sources or territories, and males may lift a hind leg to display their genitalia to attract potential mates (Vu 2011). Sometimes gray foxes groom each other, and they will participate in ritualized posture or motor patterns in threat, submissive, sexual, and aggressive contexts (Saunders, as cited in “Gray Fox” n.d.b). Juveniles are known to frequently engage in play fighting (Vu 2011).

Island Fox Social Structure

Island foxes breed once per year and are seen in pairs during January, with mating occurring from late February to early March and kits being born around late April (“Island Fox” 2021). They are typically monogamous, specifically socially monogamous, and can have a litter size as small as one kit up to five kits, and males are essential in raising the young (“Island Fox” 2021). Estrus and ovulation are induced, which is unique for canids (“Island Fox” 2021). Furthermore, it is common for males to be aggressive to females, which is also unique for canids; however, this may only apply to captive island foxes and not free-ranging island foxes (“Island Fox” 2021). The young also enjoy a stretch of extended parental care; most pups stay with their parents until the Fall (“Island Fox” 2021).

Signs of submission or dominance are exhibited in the island fox’s body posture and facial expression, while vocal communication is achieved through barking and, on occasion, growling (“Island Fox” 2021).

Swift Fox Social Structure

Swift foxes are monogamous, but may not mate with the same fox every year (Resmer 1999). Males typically breed at one year old, but females may not breed until they are two (Resmer 1999). The beginning of the breeding season for swift foxes varies across North America. In the southern part of their range in the U.S. the breeding season begins at the end of December and the start of January, whereas in Canada it begins in March (Resmer 1999). Two to six kits are born after 50-60 days, typically in mid-May in Canada, and March to early April in more southern portions of their range in the U.S. (Resmer 1999). At six to seven weeks, kits are weaned, but commonly stay with their parents until fall (Resmer 1999). Communication in swift foxes include tactile interactions and chemical signaling (Resmer 1999).

The social organization of swift foxes is female-based since females have been found to maintain territories in the absence of males, whereas males will leave in the absence of females (Kamler et al. 2004). Furthermore, while males were found to bring back food, kits were not dependent on their fathers to bring food to them (Kamler et al. 2004). Females can successfully raise kits in the absence of a father (Kamler et al. 2004). Reproductive groups are more heavily influenced by females than males (Kamler et al. 2004).

Kit Fox Social Structure

Appearance

Red Fox Appearance

Red foxes are typically larger than other North American foxes, commonly weighing 10-15 lb (5-7 kg), but can be as large as 31 lb (14 kg) (Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2022). They are about 36 to 42 in (90-105 cm) from head to tail, while they are about 16 in (40 cm) tall at the shoulder (Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2022). Red foxes’ coats are commonly reddish-orange-brown, with a white-tipped tail and black legs and ears, but the color can vary (Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2022). Black and silver variations of coat color with white, which lead to them sometimes being called silver foxes, can also be found in North America (Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2022). In North America and the Old World, there is also a more yellow-brown type of red fox with a cross between their shoulder and down their back (Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2022). They are called a brant or cross fox (Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica 2022).

Gray Fox Appearance

Gray foxes bear a similar resemblance to red foxes but are stockier (“Gray Fox (Urucyon cineoargenteus)” 2020). They are similar in height to red foxes, reaching close to the average shoulder height of red foxes, if averaging just a little less at 15 in (38 cm) (“Gray Fox (Urucyon cineoargenteus)” 2020). They can also be similar in length from head to tail, ranging from 35-45 in (89-114 cm) long (“Gray Fox (Urucyon cineoargenteus)” 2020). However, gray foxes are smaller than red foxes, at about 7-12 lb (3-5 kg) (“Gray Fox (Urucyon cineoargenteus” 2020).

These foxes have narrow and pointed muzzles as well as long ears that stand up (“Gray Fox (Urucyon cineoargenteus)” 2020). Their coats are a blend of black, white, and gray with a black stripe down their back and tail (“Gray Fox (Urucyon cineoargenteus)” 2020). They have black muzzles, white markings on their stomachs and throats, and reddish-orange coloring around their ribs and necks is a reddish-orange (“Gray Fox (Urucyon cineoargenteus)” 2020).

Island Fox Appearance

Swift Fox Appearance

Swift foxes are tiny, like the kit fox, typically weighing less than six lb and usually less than 34 in (86 cm) in length (Marks 2006). Swift foxes are a mixture of yellowish-brown and grayish-black on their back, face, tail, and thighs of their hindlimbs. Their bushy tails have a black tip, while their throats, stomachs, and chest are white (Marks 2006). Swift foxes’ sides are a bit more of an orangish-brown (Marks 2006). Swift fox coats are fluffier in the winter (Marks 2006), and short at other times of the year.

Kit Fox Appearance

Diet

Red Fox Diet

Gray Fox Diet

The diet of a gray fox includes squirrels, birds, and bird eggs which they can feast on by climbing trees (“Gray Fox (Urucyon cineoargenteus)” 2020). They also eat rabbits and rodents (“Gray Fox (Urucyon cineoargenteus)” 2020), native vegetation and fruits, such as grapes, crops (e.g., corn, peanuts) and some insects (Olfenbuttel,n.d.).

Island Fox Diet

Swift Fox Diet

Kit Fox Diet

THREATS TO FOXES

Management & Past Threats

North American foxes have faced various threats and challenges as individual species throughout their history, mainly due to human behavior and development.

Island Fox Past Threats

Historically, island fox populations had always been small and had shifted in size, but in 1994 they began dramatically declining on San Miguel, Santa Rosa, and Santa Cruz islands (“Island Fox” 2021). Golden Eagle predation on the island foxes was determined to be the cause of the unnatural and quick decline of these foxes (“Island Fox” 2021). Prior to the decline of the island foxes, Golden Eagles had not been found on these islands due to Bald Eagles deterring Golden Eagles from the islands (“Island Fox” 2021). However, due to DDT, egg collection, and hunting, Bald Eagles had been extirpated, which allowed Golden Eagles access to the islands (“Island Fox” 2021). By 1999, the island foxes on San Miguel and Santa Rosa were almost extinct (“Island Fox” 2021).

These island fox subspecies have recovered through the relocation of Golden Eagles on the island to other areas in addition to captive breeding and reintroduction of the foxes (“Island Fox” 2021). Additionally, monitoring has ensured that the fox populations continue to stabilize (“Island Fox” 2021). Bald Eagles have also been reintroduced to the islands and have continued to show they act as a deterrent to Golden Eagles (“Island Fox” 2021).

Another threat was the introduction of domestic pigs to be used as food for people, however, these pigs became feral and provided a food source for the Golden Eagles (“Island Fox” 2021). Thus, pigs were relocated in addition to Golden Eagle removal (“Island Fox” 2021).

Additional threats have included 90% of the fox population on Santa Catalina Island being decimated from canine distemper because island foxes are isolated on their islands and don’t have immunity to parasites and diseases from the mainland, which is a reason pets are no longer permitted on the islands (“Island Fox” 2021).

Swift Fox Past Threats

Throughout the 1800s and 1900s, swift foxes began to decline due to the expansion of agriculture and urban human dwellings, which led to habitat loss (Stephens & Anderson 2005, “Teacher Background Information” n.d.). They were also negatively impacted by poison intended for other animals (Stephens & Anderson 2005, “Teacher Background Information” n.d.). This indiscriminate poisoning also killed wolves–one of the intended targets (Stephens & Anderson 2005). Wolves had previously kept coyote populations in check and appeared to have paid little attention to swift foxes, so with the eradication of wolves, competition with coyotes also became a threat to these foxes (Stephens & Anderson 2005). In addition, state-regulated shooting and trapping affected these foxes (Stephens & Anderson 2005, “Teacher Background Information” n.d.). Thus, the swift fox was listed as a Threatened Species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and a Swift Fox Conservation Team was established in 1994 (“Teacher Background Information” n.d.). Following this, swift foxes were reintroduced into Montana on the Blackfeet Reservation in 1998 and then into Badlands National Park in 2002 (“Teacher Background Information” n.d.).

Current Threats

Red Fox Current Threats

Threats to the red fox include the loss, fragmentation, degradation, and exploitation of fox habitat (Hoffman & Sillero-Zubiri 2021). Indirect and direct persecution are also threats to red foxes (Hoffman & Sillero-Zubiri 2021). Additionally, in many places, foxes are viewed as pests and are unprotected (Hoffman & Sillero-Zubiri 2021), which means they can be killed year round in unlimited numbers. In addition to being legally hunted and trapped for recreation, red foxes are also the target of wildlife killing contests in many states. They are also killed by the USDA’s Wildlife Services for “damage control”.

Furthermore, two subspecies of red foxes are considered endangered in North America: the Sierra Nevada red fox (Vulpes vulpes necator) and the Cascade red fox (Vulpes vulpes cascadensis) (Reid et al. n.d. “Sierra Nevada Red Fox” n.d.). In 1980, the Sierra Nevada red fox was listed as Threatened under the California Endangered Species Act, and recently, was petitioned to be listed under the Federal Endangered Species Act (“Sierra Nevada Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes necator) and Federal Distinct Population Segments” 2022). While performing their assessment, U.S. Fish and Wildlife concluded that there are two populations of Sierra Nevada red foxes and that only one population would be listed (“Sierra Nevada Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes necator) and Federal Distinct Population Segments” 2022, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2021). Potential threats to the Sierra Nevada red fox include immigrant red foxes and coyotes expanding into their territories (leading to more competition and possible transmission of diseases), recreation and/or development (causing exposure to humans, their pets, and their vehicles, possible habituation, as well as possible exposure to fish poisoning disease), exposure to rodenticides due to farming or domesticated animals, and climate change creating a loss of boreal environment or less snow (Perrine, Campbell & Green 2010). In particular, Sierra Nevada red foxes found in the mountains are threatened by a small population size as well as climate change, which may allow for more coyotes in their habitat (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2021). The other subspecies, the Cascade red fox, is threatened by habituation to humans that brings them dangerously close to roads and humans (Reid et al. n.d.). Threats also include climate change, which reduces their habitat, and competition from an immigrant species, the lowland red fox, which was brought to Washington for hunting and fur farming (Reid et al. n.d.)

Gray Fox Current Threats

Kit Fox Current Threats

One major threat to kit foxes is the conversion of their habitat for agricultural, industrial, and urban uses (Cypher & List 2014).

Additionally, a subspecies of the kit fox, the San Joaquin kit fox, is considered endangered (“Vulpes macrotis mutica Merriam, 1902″ n.d.). The San Joaquin kit foxes were originally widespread throughout San Joaquin Valley in California, but a significant amount of the San Joaquin kit foxes’ habitat has been replaced with urban development and agriculture (Nogeire-McRae et al. 2019). Other threats to San Joaquin kit foxes include rodenticide and climate change (Nogeire-McRae et al. 2019). One study predicted climate change could be beneficial to San Joaquin kit foxes by creating grasslands from forest, thus, increasing their habitat; however, there are many reasons why it may also have a detrimental impact on the foxes, such as by leading to variation in prey due to fluctuations in rainfall (Nogeire-McRae et al. 2019). Furthermore, future reduction of the foxes’ habitat is predicted with projected land use changes to fox habitat (Nogeire-McRae et al. 2019). Solar energy, which may typically be viewed as a positive, is expanding into the habitat of these foxes, which may negatively impact their population (although it is not known with certainty) (Nogeire-McRae et al. 2019). Overall, this endangered species is facing many threats.

Swift Fox Current Threats

TIPS FOR COEXISTENCE

Foxes are found almost everywhere in many different habitats, including urban settings. So it’s important that humans learn how to best coexist with them.

You may have seen the silhouette of a red fox at night, eyes reflecting in your car’s headlights, or unexpectedly spotted a gray fox in a tree during daylight? Foxes may be active at night or during the day. The idea of foxes being out during the day may come as a surprise to some since they are mainly nocturnal in urban areas (most likely to avoid humans) (“Fox Fact Sheet” n.d.). However, it is normal for them to be active in the daytime and does not mean that the fox is sick or unwell (“Coexist with Foxes” n.d. “Fox Fact Sheet” n.d.). In fact, you may see a fox during the day because that fox feels safe and, perhaps, because food is plentiful (“Coexist with Foxes” n.d., “Fox Fact Sheet” n.d.).

Foxes are not typically dangerous to humans (“Coexist with Foxes” n.d. “Fox Fact Sheet” n.d.). The only time they pose a threat to humans is when they are rabid, which is rare but can be identified by stumbling or partial paralysis, circling or staggering, acting aggressive without reason or unnaturally tame, self-mutilating, or foaming at the mouth (Adams, n.d. “Coexist with Foxes” n.d., “Fox Fact Sheet” n.d.). If you see this, contact an animal rehabilitator or your local animal control agency (“Coexist with Foxes” n.d.).

It is important to note that red foxes are typically bolder than gray foxes, and may not retreat from humans or may sit and watch us (“Fox Fact Sheet” n.d.). Though curiosity and boldness in a red fox are considered natural, aggressiveness is not (“Coexist with Foxes” n.d.). However, boldness may also result from foxes becoming habituated to people due to people feeding them, whether intentionally (hand-feeding or leaving out food) or unintentionally (through garbage) (“Coexist with Foxes” n.d.). It is best not to feed foxes for both fox and human welfare (“Coexist with Foxes” n.d.). Even though foxes aren’t typically aggressive, a habituated fox can become aggressive (“Coexist with Foxes” n.d.). It can also be dangerous to the fox. For instance, it can bring the animal close enough to roads to be hit (Reid et al. n.d.). Additionally, not all humans may share a fondness for foxes. Some may view foxes as pests, which is dangerous for habituated foxes who have learned to approach people for food. It is also illegal in some U.S. states to feed wildlife, such as Colorado, and in certain places in Canada, like Mississauga City in Ontario, Canada (City Services 2022, “Red Fox” n.d.a).

To avoid feeding a fox unintentionally, make sure to secure your garbage in wildlife-proof containers, containers with a tight lid, or put it out the morning the garbage will be picked up (“Coexist with Foxes” n.d. “Red Fox” n.d.a). If you have a fruit tree in your yard, clean up fallen fruit off the ground to avoid attracting foxes (“Red Fox” n.d.a). If you have a bird feeder, make sure to keep the seed off the ground (“Coexist with Foxes” n.d.). If you compost, use an enclosed system and avoid adding fruit scraps or meat to your mulch or compost pile (“Red Fox” n.d.a).

Foxes can also pose a risk to pets. They can carry mange, rabies, or canine distemper (“Red Fox” n.d.c). They can also occasionally prey on small or outdoor pets, such as small adult cats, kittens, or chickens (“Fox Fact Sheet” n.d.). It is recommended to keep cats inside and dogs on a leash (“Red Fox” n.d.a, “Red Fox” n.d.c). Outdoor pets, like chickens, should be protected using sturdy pens and hutches (“Fox Fact Sheet” n.d.). An L-shaped footer that is 8 inches wide can be buried a foot deep (at minimum) to prevent foxes from digging beneath fences, further protecting outdoor pets (“Fox Fact Sheet” n.d.).

If you spot a fox, observe them from a distance. For your and the fox’s safety, don’t attempt to approach or pet the fox (“Coexist with Foxes” n.d. “Red Fox” n.d.c). However, if the fox approaches you, you may haze them by making yourself look big or making loud, constant noise (“Red Fox” n.d.c).

Foxes may also cut through people’s yards and, if so, are likely just passing through (“Adams, n.d.). Although, if a fox is hanging out in your yard or returning to it, you can make loud, constant noise by banging pots or pans to maintain a fox’s natural wariness of people (“Coexist with Foxes” n.d.). If you find a fox denning in your yard or an inconvenient spot around your house, try to refrain from hazing the fox until the kits can join parents on outings since, by that point, they will be getting close to leaving the den site (Adams, n.d.). Red foxes typically give birth in March or April, with the kits coming out of the den four to five weeks after birth, but not yet joining their parents on hunts until the age of nine weeks (Adams, n.d. “Red Fox” n.d.c). Kits are fully weaned by 12 weeks (“Red Fox” n.d.c). Gray foxes also typically give birth in March or April, but it could be earlier in some places like Texas (“Gray Fox” n.d.a, Vu, 2011). At 12 weeks, gray fox young will hunt with females (Saunders, 1988, as cited in “Gray Fox” n.d.b). So, if you want to haze and make a fox that has denned in your yard leave, it would be best to hold off until the kits are at least 12 weeks old.

A final coexistence tip is to be aware of threats and conservation issues, discussed above in the sections “Management and Past Threats” and “Current Threats.” By knowing the threats and conservation issues foxes face, we can be mindful of how our actions impact them, and take action to help different fox species.

LITERATURE CITED

Adams, B.W. (n.d.). What to do about foxes. The Humane Society of the United States. https://www.humanesociety.org/resources/what-do-about-foxes

Baker PJ, Harris S (2004) The behavioural ecology of red foxes in urban Bristol. In: Macdonald DW, Sillero-Zubiri C, editors. Biology and conservation of wild canids. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 207–216.

City Services. (2022, May 20). What does the fox say? Keep me wild–Don’t feed me! Mississauga. https://www.mississauga.ca/city-of-mississauga-news/news/what-does-the-fox-say-keep-me-wild-dont-feed-me/

Coexist with foxes. (n.d.). North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission. Retrieved April 3, 2023, from https://www.ncwildlife.org/Portals/0/Learning/documents/Profiles/Mammals/Co%20exist%20with%20foxes_Update-2018.pdf

Cypher, B. & List, R. (2014). Vulpes macrotis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-3.RLTS.T41587A62259374.en

Dorning, J. & Harris, S. (2019). Understanding the intricacy of canid social systems: Structure and temporal stability of red fox (Vulpes vulpes) groups. PLoS One, 14(9). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6738593/#pone.0220792.ref045

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2022). Red Fox. In Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/animal/red-fox-mammal

Fox. (2023, January 22). In New World Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 4, 2023, from https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Fox#Classification

Fox fact sheet. (n.d.). Greenwood Wildlife Rehabilitation Center. Retrieved April 3, 2023, from https://www.greenwoodwildlife.org/wp-content/uploads/FoxFactSheet-1.pdf

Gray fox. (n.d.a). Wildlife Science Center. Retrieved January 29, 2023, from https://www.wildlifesciencecenter.org/gray-fox

Gray fox. (n.d.b). State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Retrieved March 29, 2023, from https://www.esf.edu/aec/adks/mammals/gray_fox.php

Gray fox (n.d.c.). Canid Specialist Group. Retrieved April 2, 2023, from https://www.canids.org/species/view/PREKJP597461

Gray fox M074 (Urocyon cinereoargenteus). (n.d.). USDA Forest Service. Retrieved March 3, 2023, from https://www.fs.usda.gov/psw/publications/documents/psw_gtr037/mammals/m074.pdf

Gray fox (Urucyon cineoargenteus). (2020, August 21). National Park Service, Retrieved February 5, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/jeca/learn/nature/gray-fox-urucyon-cineoargenteus.htm

Hammerson, G. & Cannings, S. (2023, March 3). Vulpes velox. Nature Serve Explorer. https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.104178/Vulpes_velox#Authors_and_Contributors

Hofman, C.A. Rick, T.C. Hawkins M.T.R. Funk, W.C. Ralls, K. Boser, C.L. Collins, P.W. Coonan T. King, J.L. Morrison, S.A. Newsome, S.D. Sillett, T.S. Fleischer, R.C. & Maldonado, J.E. (2015). Mitochondrial genomes suggest rapid evolution of Dwarf California Channel Island Foxes (Urocyon littoralis). PLoS ONE, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0118240

Hoffman, M. & Sillero-Zubiri. (2021). Vulpes vulpes. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T23062A193903628.en

Island fox. (2021, May 21). National Park Service, Retrieved February 5, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/places/island-fox.htm

Island fox. (2022, November 21). National Park Service, Retrieved March 21, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/chis/learn/nature/island-fox.htm

Kamler, J.F. Ballard, W.B. Gese, E.M. Harrison, R.L. Karki, S. Mote, K. (2004). Adult male emigration and a feamle-based social organization in swift foxes, Vulpes velox. Animal Behaviour. 67(4), 699-702, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.08.012

Kit fox. (2016, August 23). National Park Service, Retrieved February 12, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/whsa/learn/nature/kit-fox.htm

Kitchen, Ann, Gese E.Karki, S. M. Schauster, E.R. (2005) Spatial Ecology of Swift Fox Social Groups: From Group Formation to Mate Loss, Journal of Mammalogy, 86(3), 547–554, https://doi.org/10.1644/1545-1542(2005)86[547:SEOSFS]2.0.CO,2

Leishman, C. (n.d.). Gray Fox. Nature Canada. https://naturecanada.ca/discover-nature/endangered-species/gray-fox/

Lucenti S.B. & Madurell-Malapeira. (2020). Unraveling the fossil record of foxes: An updated review on the Plio-Pleistocene Vulpes spp. from Europe. Quaternary Science Reviews, 236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106296

Marks, R. United States Natural Resources Conservation, & Wildlife Habitat Council. (2006). Swift Fox (Vulpes velox): (Fish and Wildlife Habitat Management Leaflet, no.33). Natural Resources Conservation Service. Retrieved February 15, 2023, from https://permanent.fdlp.gov/lps101810/8043.pdf

Meaney, C.A. Reed-Eckert, M. & Beauvais, G.P. (2006, August 21). Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotis): A Technical Conservation Assessment. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5181917.pdf

Natural history. (n.d.). Center for Biological Diversity. Retrieved March 24, 2023, from https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/mammals/island_fox/natural_history.html

Nogeire-McRae, T. Lawler, J.J. Schumaker, N.H. Cypher, B.L. Philips, S.E. (2019). Land use change and rodenticide exposure trump climate change as the biggest stressors to San Joaquin kit fox. PLos ONE, 14(6). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214297

Olfenbuttel, Colleen. (n.d.) “Gray Fox”. North Carolina Wildlife Profiles. Retrieved May 23, 2023 from https://www.ncwildlife.org/portals/0/learning/documents/profiles/gray_fox.pdf

Patton, A. (2008). Vulpes macrotis. Animal Diversity Web. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Vulpes_macrotis/

Perrine, J. D. Campbell, L. A. & Green, G. A. (2010, August). Sierra Nevada Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes necator): A Conservation Assessment. USDA. https://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentID=23994

Reid, M. Chestnut, T. Swinney, D. Jenkins, K. & Griffin, P. (n.d.). Human Influences on the Cascade Red Fox. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/gis/storymaps/cascade/v1/index.html?appid=aa0c69b1af5e4503b2659d65bf409fd6

Red fox. (n.d.a). Colorado Parks and Wildlife. Retrieved April 7, 2023, from https://cpw.state.co.us/learn/Pages/LivingwithWildlifeRedFox.aspx

Red fox. (n.d.b). New York Department of Environmental Conservation. Retrieved March 20, 2023, from https://www.dec.ny.gov/animals/9354.html

Red fox. (n.d.c). NYC. Retrieved April 7, 2023, from https://www.nyc.gov/site/wildlifenyc/animals/red-foxes.page

Resmer, K. (1999). Vulpes velox. Animal Diversity Web. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Vulpes_velox/

Sierra Nevada Red Fox. (n.d.). California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved February 17, 2023, from https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Mammals/Sierra-Nevada-Red-Fox

Sierra Nevada Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes necator) and Federal Distinct Population Segments. (2022, May 9). California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved February 20, 2022, from https://wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/News/sierra-nevada-red-fox-vulpes-vulpes-necator-and-federal-distinct-population-segments

Sovada, M.A. Woodward, R.O. & Igl, L.D. (2009). Historical range, current distribution, and conservation status of the Swift Fox, Vulpes velox, in North America. Canadian Field-Naturalist, 123(4), 346-367. https://doi.org/10.22621/cfn.v123i4.1004

Stephens, R.M. & Anderson, S.H. (2005, January 21). Swift Fox (Vulpes velox): A Technical Conservation Assessment. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5181934.pdf

Teacher background information. (n.d.). National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/common/uploads/teachers/lessonplans/SwiftFox_TBI.pdf

Urocyon Baird, 1857. (n.d.). Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=180608#null

Urocyon cinereoargenteus (Schreber, 1775). (n.d.). Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved February 3, 2023, from https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=180609#null

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (2021). Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; Endangered species status for the Sierra Nevada distinct population segment of the Sierra Nevada red fox. Federal Register. Federal Register, 86(146), 41743-41758. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/08/03/2021-16249/endangered-and-threatened-wildlife-and-plants-endangered-species-status-for-the-sierra-nevada

Vu, L. (2011). Urocyon cinereoargenteus. Animal Diversity Web. https://animaldiversity.org/accounts/Urocyon_cinereoargenteus/

Vulpes macrotis Merriam, 1888. (n.d.). Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=180606#null

Vulpes macrotis mutica Merriam, 1902. (n.d.). Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved February 13, 2023, from https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=202397#null

Vulpes velox (Say, 1823). (n.d.). Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved February 9, 2023, from https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=180607#null

Vulpes vulpes (Linnaeus, 1758). (n.d.). Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved February 3, 2023, from https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=180604#null

White, P.C.L. & Harris, S. (1994). Encounters between Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes): Implications for Territory Maintenance, Social Cohesion and Dispersal. Journal of Animal Ecology, 63(2), 315–327. https://doi.org/10.2307/5550

Whiteside HM, Dawson DA, Soulsbury CD, Harris S (2011) Mother Knows Best: Dominant Females Determine Offspring Dispersal in Red Foxes (Vulpes vulpes). PLOS ONE 6(7): e22145. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0022145

Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). Carnivora. In Wilson, D.E. & Reeder, D.M. (eds.). (2005). Mammals Species of The World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed., pp. 532-628). The John Hopkins University Press.