From her roots in Queens, New York, to the savannahs of East Africa, to the urban landscape of California’s Bay Area, Dr. Christine E. Wilkinson has always been fascinated by wildlife.

Currently, Christine is working as a postdoc at the University of California, Santa Cruz and the California Academy of Sciences. She is a conservation scientist, carnivore ecologist, and urban ecologist who is passionate about taking an intersectional approach to science, incorporating ethics, justice, and community voices into her work to affect equitable conservation outcomes.

Christine co-founded Black Mammalogists Week in 2020, and created Queer is Natural TikTok series to show that same-sex sexual behaviors and gender fluidity are common across the animal kingdom. In 2023, Christine was awarded the third annual Rising Black Scientists Award by Cell Press, Cell Signaling Technology (CST), and the Elsevier Foundation.

Coyotes have become central to Christine’s research in the Bay Area and Los Angeles, where she collaborates with local communities, organizations, and agencies on data collection, outreach, and management efforts. She and her colleagues collate Bay Area-specific coyote information on their website, BayAreaCoyote.org, where they encourage community members to report coyote sightings to assist with future human-coyote coexistence efforts in the Bay. This June, she will co-host a symposium on coyotes at the International Urban Wildlife Conference, where she will help guide discussions around how to best engage communities in effective coyote data collection and coexistence measures (Project Coyote Carnivore Conservation Director Renee Seacor will also be presenting at this symposium on best practices for creating and implementing outreach programs aimed toward coyote coexistence).

In celebration of Coyote Awareness Week, the Project Coyote team was honored to speak with Christine about the evolution of her research, her connection with coyotes, and her aspirations for the future of human-wildlife coexistence. We hope you enjoy learning more about Christine and her important work in the Q&A below.

Q: How did coyotes come to be a major focus of your research? What are some of the central questions you are most interested in or feel are most important to address current challenges facing wild carnivores?

A: I have spent my entire career working in various places across the globe to holistically understand the dynamics driving human-wildlife conflict, and to seek sustainable and equitable mechanisms for coexistence. Having worked on spotted hyenas in Kenya, to me coyotes seem to be the North American equivalent as far as people’s negative perceptions of the species. I began working with coyotes because I had worked in East Africa for many years, and really wanted to work within my own community (the San Francisco Bay Area), where coyotes are one of the main species routinely involved in human-wildlife interactions. Most of the questions I’m interested in center around how we can create cultures of coexistence with carnivores, which involves prioritizing the wellbeing of both people and wildlife by using an environmental justice lens while examining these conservation challenges.

Q: Do you have a memorable experience related to interacting with or observing a coyote?

A: Every moment I spend with a coyote is memorable. Recently, I was in Santa Cruz, California, on a very rainy day and saw a coyote at the UC Santa Cruz Coastal Campus. I stopped to watch the animal, who seemingly gave absolutely no thought to the pouring rain, and instead did several glorious hunting pounces in an attempt to catch gophers. The coyote’s unwavering energy, with its silver-beige fur glinting in the rain, brought some magic on such a dreary morning.

Photo by Nicole Wilde, #CaptureCoexistence Contributor.

Q: What do you and your colleagues hope to achieve during the Coyote Management Symposium at the International Urban Wildlife Conference this June?

In this full-day symposium, Dr. Phoebe Parker-Shames, Tali Caspi, and I hope that we can bring together many different types of coyote researchers and conservation practitioners in the same space, thereby allowing us to learn from one another about best practices, research and management gaps and challenges, and how we might best work together across regions and sectors to more effectively understand and foster urban human-coyote coexistence.

My presentation, “Coyotes don’t pay taxes: Addressing challenges in interpreting community-curated datasets on urban human-coyote interactions,” will focus on the challenges in interpreting community-curated datasets for urban human-coyote interactions. [Community-curated datasets are collections of data created, maintained, and/or shared by a group of users or a community]. These datasets can tell us just as much about the data providers’ values and perspectives as they can about the human-wildlife interactions themselves. Additionally, community-curated datasets are shaped by the goals of that particular community, which can influence their interpretation. My hope with this presentation is to explain how we addressed some of these challenges in our 2023 study on human-coyote interactions in San Francisco, and also propose some ideas to attendees about how to collaborate and streamline our efforts across cities.

Q: The results from your most recent publication, “Environmental Health and Societal Wealth Predict Movement Patterns of an Urban Carnivore,” were surprising to some people. What did you expect to find, and how might the results shift perceptions or help dispel some of the assumptions about coyote behavior and human-coyote interactions?

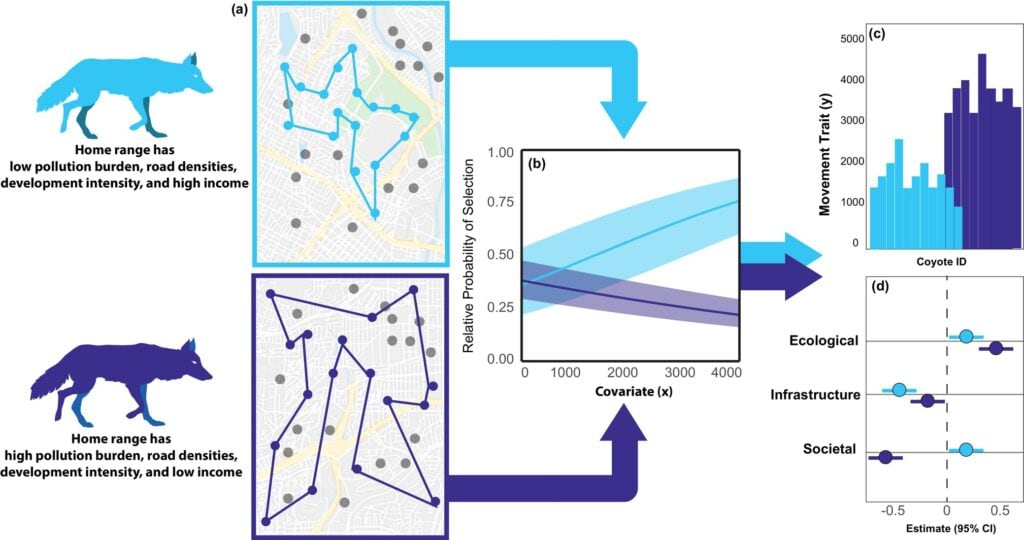

A: While most previous studies on coyote movement have focused on ecological factors, such as green spaces, and to some extent linear infrastructure like roads, for this project we also integrated societal factors (including wealth, pollution burden, human population density) into movement models and demonstrated that these factors were important for predicting urban coyote movement. Importantly, we also found that coyotes in more anthropogenically burdened areas (meaning areas with a higher pollution burden, lower median income, higher human population density, etc.) had, on average, larger home ranges, greater mean daily displacement (a measure of exploration), and longer step lengths (which could be indicative of speed).

This figure from Wilkinson’s publication shows how urban coyotes may move and select habitats based on human-made and environmental factors. In more developed and polluted areas, they tend to roam larger areas, move more frequently, and rely more on natural features while avoiding human-related elements.

All of these findings point to more burdened coyotes likely needing to go further afield to get the resources they need, which may have energetic consequences. This has opened up a wide range of follow-up questions both for coyotes and for other urban species. I think one of the biggest broader implications from this project is that we have provided more empirical evidence suggesting that urban wildlife face risks and consequences from the same inequities that people also face. Designing resilient, wildlife-friendly cities requires addressing the societal (in)equities that impact both people and wildlife.

Q: As a member of our peer-review team for Project Coyote’s Model Coyote Coexistence Plan, can you describe the process of creating guidance like this, and on the importance of communities adopting coexistence plans in general?

A: I was impressed with the comprehensiveness of Project Coyote’s Model Coyote Coexistence Plan, and even more pleased with the willingness of Project Coyote to take into account detailed, and sometimes difficult, feedback from myself as a scientist and human-wildlife interactions specialist, as well as, I’m sure, many other contributors. It isn’t easy to make a coexistence plan that considers the science, the varying social-ecological contexts across regions, and people’s extraordinarily nuanced and varied perceptions and desires, but I think Project Coyote has created one of the best such resources. Coexistence is a two-way street, and creating cultures of coexistence with coyotes and other controversial wildlife will require us to do better at creating, agreeing to, and funding coexistence plans.

Q: What draws you to coyotes? What would you hope others see in these animals as we work towards coexistence?

Coyotes are extraordinarily resilient, intelligent, behaviorally flexible animals. They have managed to persist, and even expand their ranges, despite facing numerous adversities and still being reviled by many people in the present day. In fact, many animals that are misunderstood and persecuted are often viewed poorly simply because they are able to take what people throw their way and still survive—or sometimes even thrive. And sometimes people don’t like that, especially for conflict-prone species! But I think we have a lot we can learn from such highly adaptable, resilient, non-human animals.

Photo by Lauren van Schijndel, #CaptureCoexistence Contributor.