Notes From The Field Blog by Francisco J. Santiago-Ávila, Midwest Science & Conservation Manager for Project Coyote & The Rewilding Institute.

In my prior blog entry, after introducing myself, I touched on both Euro-North American and Ojibwe worldviews, specifically in relation to wolves. The objective was to highlight how worldviews influence our values and motives, including those guiding science. Therefore, science will always be partial to worldviews, which suggests the foundational discussion within conservation should be about worldviews. In that entry, I suggested that Ojibwe views of wolves were more accurate, caring and respectful than those of Euro-North American managers when assessed from who we know wolves are. Yet, the Ojibwe and other Indigenous worldviews are not the only ones who consider wolves as persons with whom we should cultivate caring and respectful relationships.

Some Western worldviews align with such an understanding of ma’iingan (‘gray wolf’ in the Anishinaabe language), most notably animal and nature ethics perspectives which are interested in cultivating caring and just relationships with nonhumans as individuals and communities. Within these perspectives, an ecofeminist nature ethic has much to contribute to promoting coexistence, as it rejects oppressions based on linked value oppositions (male/female, white/non, reason/passion, human/nature), conceives of the self in relationship with others and thus removes a presumption of conflict between parts of a whole.

Such a worldview is rooted in an intersectional, ecofeminist ethic of care that involves beginning ethically from a position in which we don’t view ourselves as having an assumed, self-proclaimed right to decide over the lives of other animals, and valuing those animals as vulnerable, different, dependent and embodied agents.

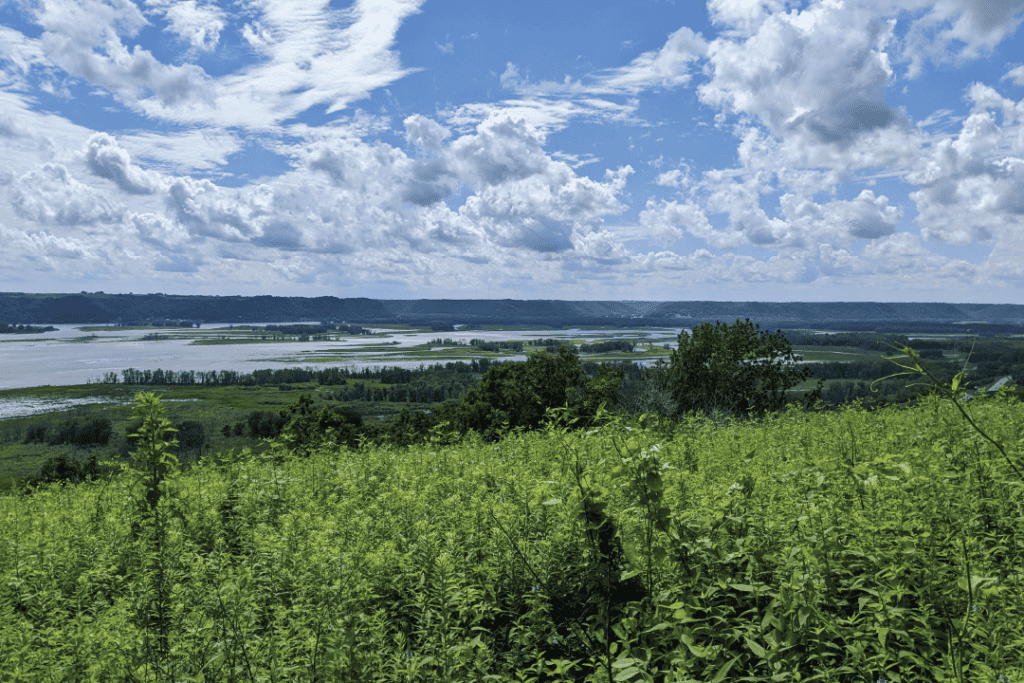

Rush Creek Park

In my scholarly work, I tie the ecofeminist nature ethics of Mary Midgley, Karren Warren, Marti Kheel and Val Plumwood, to name a few, with multispecies justice through the concepts of respect and dignity. The reasoning is that an ethic of care acknowledges the dignity of otherness and differences. Dignity means that those others are worthy of respect, and respect means that we have ‘due regard’ (read ‘adequate consideration’) for their claims. These concepts are intimately tied to justice because justice concerns ‘what we owe to and are owed by others’ in our communities, and other animals have always had claims and been part of those communities, indoors and outdoors. So, promoting multispecies justice entails a fair balancing of the claims of humans and nonhumans in our mixed-moral community, rather than the dismissal of the urgent claims of animals (to life, wellbeing, autonomy) in favor of any human ones (e.g., to minor comforts or enjoyments).

The acknowledgment of other animals as part of our mixed-moral community, along with recognizing their traits and relationships, makes animal oppression in all its forms a social justice issue rather than simply an environmental or animal issue. As with other humans, we should recognize that our ethical duties towards nonhumans go beyond ecology or sustainability.

Justice can and ought to apply to our relationship with nonhuman beings, and we should reckon with this realization. This reckoning demands we give up comforts derived from animal oppression.

Such a worldview also opens up new areas for intersectionality: to grasp connections among oppressions to humans, animals and nature. As noted by ecofeminists and others, there are deep philosophical and psychological connections between those worldviews dismissive of animals and those that marginalize other humans, such as racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism and social dominance orientations like right-wing authoritarianism.

In all cases, an arbitrary but enshrined quality is prized above all others, differences are devalued and what is deeply shared – life, wellbeing, agency – is dismissed. The clearest example of this dismissal may be how industrial animal agriculture blatantly dismisses the claims of the nonhumans involved through both bodily violation and psychological harm, all the while creating massive ecological harms that disproportionately impact not only nonhumans (wolves included), but also the health and livelihoods of the most marginalized and vulnerable communities through both local and global environmental degradation. All of this harm is undertaken for products that have massive adverse impacts on human health (e.g., consumption of animal products increases the risk of various cardiovascular diseases, among other issues). Another example is the still widespread and exclusionary conservation discourse used to promote widespread harm to feral animals and immigrant species through invidious terms such as ‘invasive,’ ‘pest,’ ‘exotic,’ when evidence points to <1% of immigrant species as having ecologically concerning effects on ecosystems.

Related to wolves and First Nations, advocates for wolf hunts in Wisconsin wolf management frequently explicitly called for violating Ojibwe usufruct (a legal term defining the right to use and benefit from something though it belongs to another) treaty rights and deny them wolf permits (intentionally claimed by the Ojibwe without actually killing wolves, to reduce the number of wolves that could be hunted) because the state wanted to kill more wolves. In fact, the state actually repeatedly denied the Ojibwe such rights. More recently, both the Trump and Biden Administrations neglected to consult with tribes before removing ESA protections for wolves, despite full knowledge of the cultural impact of policies allowing the widespread killing of their relatives.

Eagle Point Park

So how do we integrate this ethical and scientific knowledge and employ it for rewilding through our Heartland Rewilding Initiative? How do we begin promoting a “wilder, more beautiful, biologically diverse, and enduring Mississippi River Watershed” for all beings? We can interpret rewilding through an ecofeminist lens, using an ethic of care and multispecies justice that converges with deep ecology insights. Consider the following statements by deep ecologist philosopher Arne Næss: “Every living being should have an equal right to live and flourish,” therefore human destructive lifestyles should be precluded because “diversity implies self-determination.” Self-determination is inherent in nature, and diversity of life flourishes when we respect the autonomy of nonhuman individuals and communities, rather than when we restrict it and bend it to human will. Similarly, deep ecology writer and activist Gary Snyder says that “wildness… is the world.” If so, then rewilding is a worldview, and we need to start by integrating it; we start by rewilding ourselves.

For me, rewilding is not about how to make nonhuman nature follow human-centered categories and values, or how to bend the will of other beings to ours. Instead, rewilding could be conceived as allowing for beings, human and nonhuman, to thrive in all their diversity without imposing on them an arbitrary, dismissive human will or value, including through categories like ‘nativeness’ or ‘domesticity.’ This must include balancing human and nonhuman claims, knowing that most nonhumans—along with many marginalized humans—have much more to lose. Foregrounding the claims of the most vulnerable is vital. Exclusionary impositions and exploitation in all its forms are opposed to wildness and rewilding, again pointing to the need for respect and intersectionality for real progress: “the absolutely highest level of self-realization cannot be reached by anybody without all others also reaching that level.” (A. Næss)

Moreover, wildness is unrestricted. Snyder mentions “deer mice on the back porch, …pigeons in the park, spiders in the corners” as examples of wildness. Our vision of Heartland Rewilding adds to Snyder’s vision: peaceful coexistence with wild relatives like neighborhood coyotes, and enough habitat free from human domination for large carnivores and other wildlife to flourish and self-regulate their lives and relations.

Such rewilding requires fostering coexistence through all landscapes. The objective is to allow wildness to manifest itself as it will.

To accomplish that vision, we are employing all tools at our disposal, both ethical and scientific. We are rewilding worldviews by foregrounding the claims of large carnivores, centering their care and respect as essential components of coexistence. In policy, we are advocating for full protections for carnivores across the Midwest, in addition to the establishment of cores and corridors that would allow them to recolonize territory if they are so inclined. We are educating on non-lethal and least-harmful conflict mitigation measures with carnivores while clearing up misperceptions of carnivores’ risk to humans. We are collaborating on scientific research on large carnivore mortality in Midwestern states and beyond. And we’re only getting started.

If wildness is the world, then rewilding requires humans to respect nonhuman beings. It requires us to restrain human will and stop destructive practices – even traditional ones if conditions no longer justify them. And, crucially, it requires intersectionality, so that our entire community of life can flourish.