Notes From The Field Blog by Michael Walker, with an introduction by Camilla Fox, Project Coyote Executive Director

Today’s Notes from the Field blog introduces our newest Artist for Wild Nature, Michael Walker. Michael’s most recent project, a musical journey called Canyon, Illuminant, effortlessly draws us into deep time with hypnotic imagery of “a day in a life” of this canyon, set 15,000 years ago.

His music is masterful storytelling that is able to deliver us into a dreamlike realm of creative connection with animals and our earth. Paired with his sophisticated and factual writing — that still manages to evoke an aspirational love of nature — this intersection of musical storytelling and conservation is immensely powerful.

Here in deep time, we become explorers of a sensory world in which imagination and the senses reveal the lives of animals in their element. The music draws us into stories that could be from eons ago or happening now, as we seek solace in a world out of balance.

I hope you enjoy this Notes from the Field blog about this dimension of soulful experience and timeless connection from Michael himself.

For the wild ones – and for art that transcends the mundane,

Camilla

Founder & Executive Director

I am honored to introduce myself as the Artists For Wild Nature program’s newest inductee. For those new to my work, I hail from Amarillo, Texas. I am a musician, musical producer, painter, flower arranger, photographer, and writer. Buddhist meditation is an integral practice to my creative work and my life.

I was fortunate to study at one of Texas’ finest research universities, Texas State University, nestled on the San Marcos River in the beautiful Texas Hill Country. I discovered the world through my coursework; English, Archaeology, Philosophy, and Art. Artistic work has always been my passion and I have been steadfast in my commitment to creating. I began my career in a robotics laboratory, spent time in the software industry, and found a vocation in the construction science field for shy of a decade. In both study and industry, I find myself in spaces where creativity and science converge.

Liminal spaces are significant; therein we can deeply communicate with one another. Finding the human element in all the data crunching—artistic interpretations of scientific discovery—makes for compelling stories. My focus in work and art centers on that kind of storytelling.

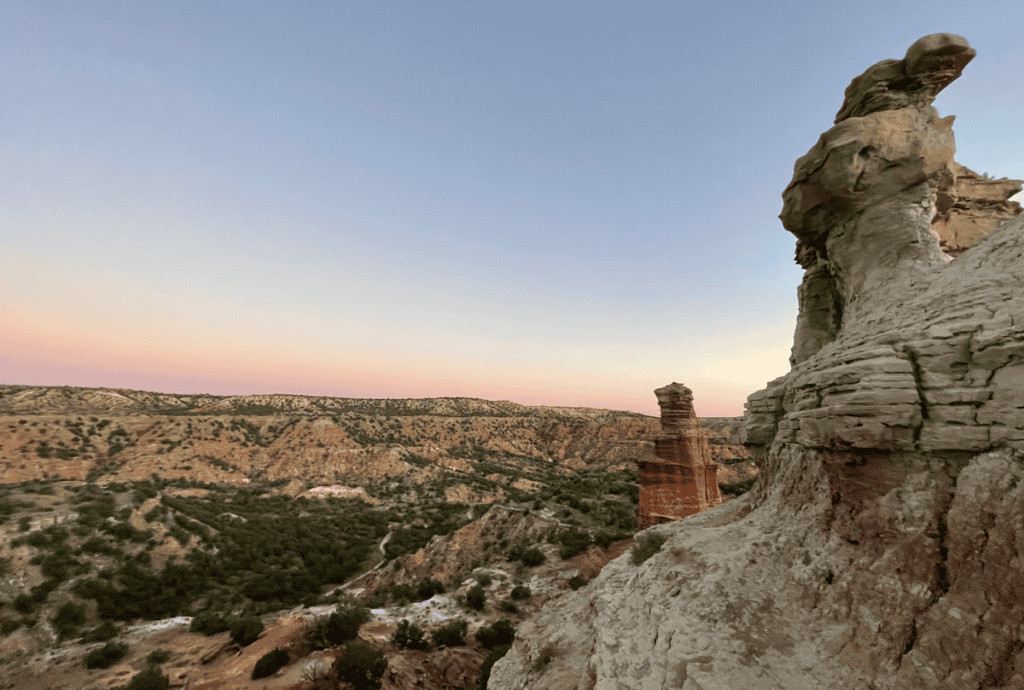

The Texas Panhandle’s landscape has also been a constant theme in my creative work. Growing up next to Palo Duro Canyon was a gift. Against painted canyon walls, I spent my childhood among windswept juniper, yucca, sagebrush, prickly-pears, and lavish grasses. I’ve encountered innumerable turkeys, mule deer, black widows, roadrunners, rattlesnakes, rabbits, and coyotes. The immense, often unseen, ecosystems of the Llano Estacado made a profound impact on my sense of self and world. That tableau has become elemental and indistinguishable from my identity. It has taken my entire life to this point to understand and unpack the gravitational pull of that land.

One of my earliest memories, and a story which my grandmother loves to regale, is waking up to the cacophony of coyotes. I was born while my parents were still in school. They were young college students endeavoring to finish their degrees with a toddler in tow. During final exam season, I often stayed with my mother’s parents, who lived near a rural reservoir formed on the Salt Fork of the Red River. On such an occasion, sleeping soundly between my grandparents, the coyotes’ wild yips startled me awake. That coyote-ness is a haunt children never forget. Nose-to-nose with my grandmother, I woke her with little hands and demanded to know “what was that!?“

Coyotes have been both a physical and spiritual presence in my life since.

So naturally, it was through Dan Flores’ phenomenal works—Coyote America, American Serengeti, and Caprock Canyons—that I gathered inspiration for my most recent musical endeavors. He has no doubt inspired many of you as well and has been an instrumental element in the spirit of Project Coyote itself. In correspondence with Professor Flores, we discussed the importance of cross-pollination, not only between scientific and artistic communities, but also between different kinds of creative work. One media may find locus in the imagination that another does not. Together, the stories we tell take on more depth and engage broader audiences.

Discovering the “Artists For Wild Nature” program then felt as surprising and natural as that first coyote memory. I am thrilled to be a part of such a diverse and powerful collective of creative humans. My intention is to contribute work that brings attention to issues of ecology, fauna, and land in ways that are not obvious. Through contemplative practice, I will engage with the ideas that come in liminal spaces and tell stories that (hopefully) move my audience to action.

I hope you enjoy this journey alongside me. You can read more about recently released work, as well as in-progress work, below.

Stay well, be in touch, and sojourn well,

M. Walker

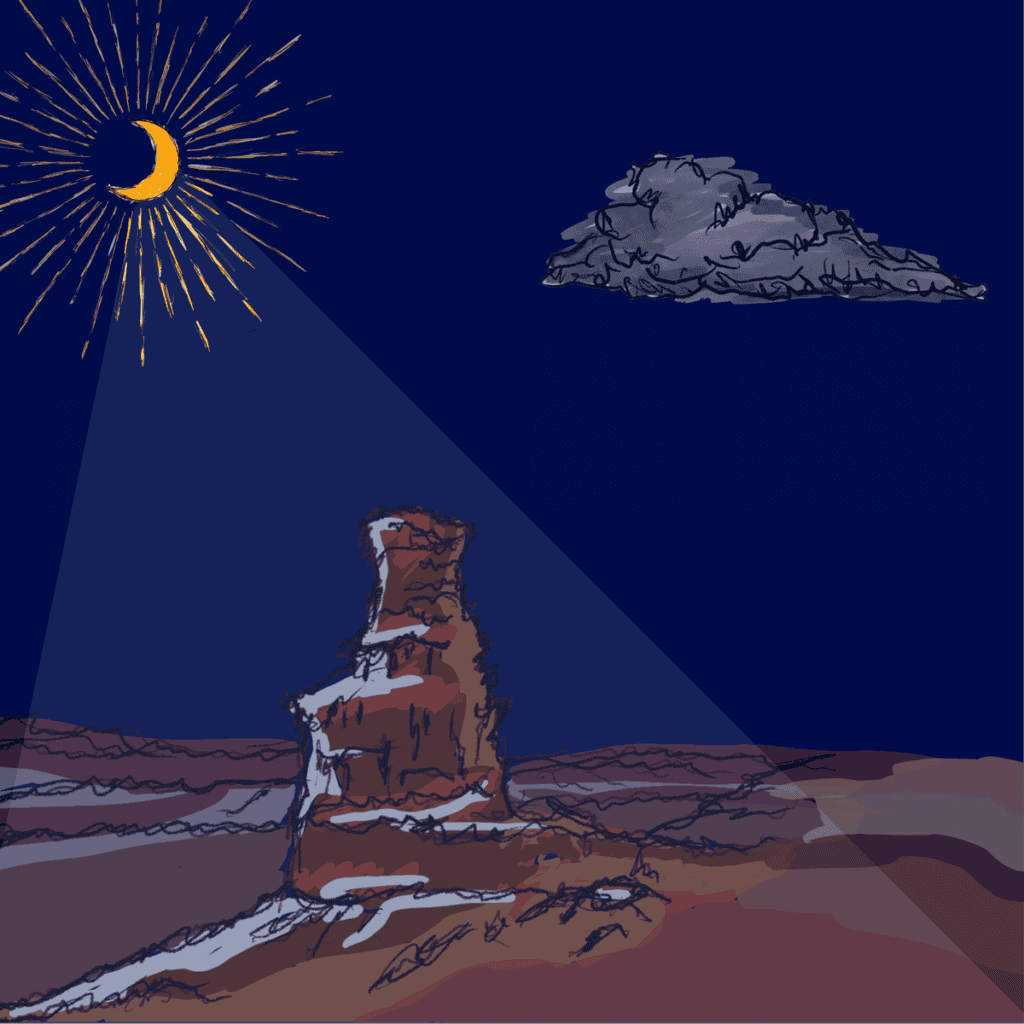

Canyon, Illuminant

(released January 8th, 2022)

The album is an instrumental exploration of pre-historical megafauna in Palo Duro Canyon. What was the place like 15,000 years ago, before humans set foot there?

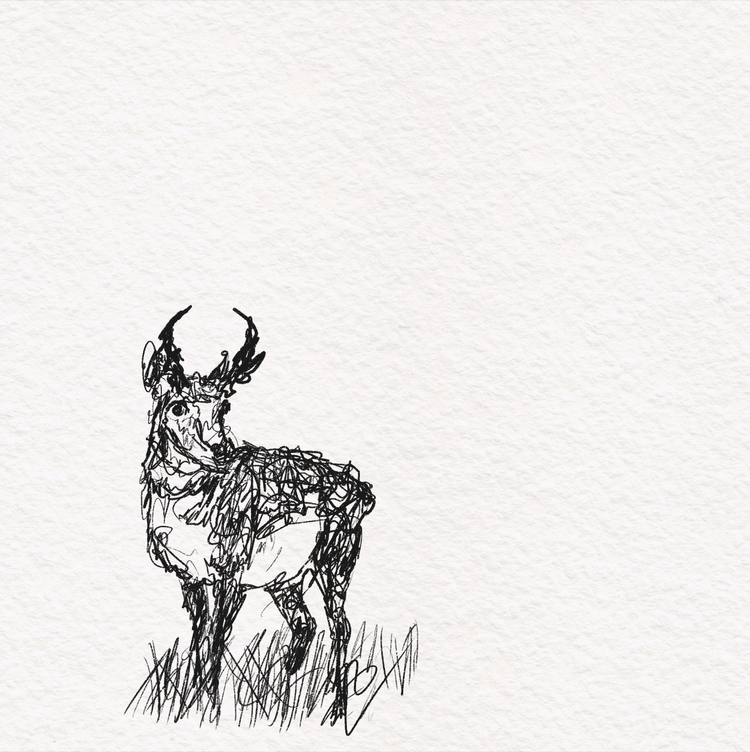

Across the region’s profusion of canyons teemed bison, red wolf, elk, fish, bobcats, deer, birds, coyote, pronghorn, chaparral, cougars, grizzlies (yes, grizzlies), and reptiles in such immense numbers that much later, well after human occupation and European colonization had begun, John James Audubon was so moved by the site of their density on these interrupted prairie lands that he wrote, “it is impossible to describe or even conceive the vast multitudes of these animals.” To simply imagine these animals living as they did before us, competing for the concentrations of resource wealth that dotted the vast plains along its watersheds and especially in the sheltered canyonlands, is difficult to do.

Given such wealth, it is no wonder that humans eventually sought out that great hiding place on the great American Serengeti, feeling somewhere deep down an ancestral connection to the cradle of humanity far across the Atlantic Ocean. Unfortunately, our sense of possession, of separation, and of a desire to contain this place — a place older than anyone can properly imagine — has utterly decimated the populations of those great animals. The ecological niches this incredible biomass once filled have given way to commercialized, mono-cropped farming practices, the same that caused The Dust Bowl.

The scale of the ecological disruption we caused the great prairie lands on the North American continent is difficult to grapple with. The percentage of indigenous grasslands that remain today are often below 20% depending on the state. Much of the land where I grew up is now checkered patterns of plowed cotton fields or otherwise cultivated agricultural tracts. There are robust studies on this land-use strategy’s impact on climate change and even the federal government talks a big game about its preservation out of one side of its mouth, while utterly neglecting broader potential restoration and re-wilding out of the other. Yet, we continue to neglect the grasslands, including the canyonlands of the Llano Estacado, which once housed unimaginable biodiversity.

At least we were sensible enough to hold on to a small parcel of these canyonlands to admire and hold in heart, now called Palo Duro Canyon State Park, administered by the state of Texas’ Parks and Wildlife department. If we’re lucky, the state will continue to expand the park’s territories all the way down to Caprock Canyon, where some bison still roam in that state park. Just as countless other humans before me, I have walked the trails and slept under the stars in Palo Duro Canyon since I can remember. The state park and the adjacent private canyonlands, in which I was fortunate enough to camp and play as a child, were essential loci for my understanding of the land where I was born and its great many workings. Like O’Keefe, it is also my spiritual home. She put it quite well when she wrote, “it is absurd the way I love this country.” And though I now have lived 500 miles away for some 16 years, that canyon still has a gravitational pull on me.

In October of 2021, I took a pre-dawn run on the canyon floor to the famous butte called The Lighthouse. It was cold, windy, and I was alone (without humans at least) for several hours before the sun peeked over the canyon walls and began to warm the scene. As I made my way down the trail, it struck me how powerful the canyon has been long before human presence and will continue to be long after we cease to exist. Imaginary flashes of that same wilderness and its ceaseless movements without anyone else around. There was a primal quality to that experience which I will never forget. The canyon struck me that morning and left a new impression of my spiritual home.

O’Keefe called it “a burning, seething cauldron, filled with dramatic light and color.” In many ways, because of its unique geography contrasted to the endless sea of grasses surrounding it, the undulating sweeps of the canyonlands are an evolutionary crucible. Whether special survival or spiritual growth, the canyon offers itself up almost sarcastically with the knowledge that it will remain though all else returns to dust. But if you go there and listen carefully, it might reveal itself to you. It may tell of its history, which predates time. It may present itself in the form of an ancient spiritual home of terrestrial poetry. If you’re not paying attention, you’re likely to toss your water bottles into trailhead trash bins and simply drive back to town for dinner, ignorant of the staggering life that once swelled and brimmed from within canyon walls, none the wiser for having visited.

This album intends to evoke a sense of that place and its quality of deep time. It is a tableau of a pre-anthropic morning in this great canyon: an instrumental series of vignettes, close-ups of scenes in a morning that none of our most distant ancestors could even remember. I recorded these songs in my home studio, supported by J. Combs, who generously helped me weave brilliant synthesizer accompaniment into my largely acoustic arrangements. The instrumentation is kept simple and consistent across tunes – piano, guitar, bass, drums, violin, and synthesizer — to represent the strata that you find in the canyon walls. Each number focuses on a character or set of characters in the canyon, doing what they do at dawn. I tend to write a lot of songs about the moon and thought that would be a good place to start.

I hope you enjoy these terrestrial and bestial stories. This is not a typical record and I don’t expect it to ever experience commercial success, but that’s not even remotely its purpose. It is an invitation into a kind of music and art that has little to do with systems of commerce, which we’ve established will be long outlived by the canyonlands in view across these tunes. It’s tempting to put on instrumental music while we fold our laundry, something we don’t have to pay attention to. Resist that urge and really listen. Pay attention to what you feel when you listen. Do you see the great species that our own destroyed? How might you contribute to this ecology’s restoration?

On The Boards – Work Upcoming

The Canyon Trilogy

This instrumental project, spanning three albums, explores the canyons and badlands of the Llano Estacado across time. Each album is accompanied by my own visual work — sketches, paintings, and photographs.

- The first record, Canyon Illuminant, is a musical exploration of prehistoric megafauna in Palo Duro Canyon, my spiritual home.

- Creating space for the imagination to visualize what the canyon looked like before humans had the chance to wreck it.

- The second record, yet-to-be-named, is in production and explores a tragic and consequential moment in our history, The Red River War.

- Instrumental and experimental, the music examines the range of human emotions that culminated in the extirpation of the Indigenous people and wildlife of the Llano Estacado in the name of progress.

- The final record, in planning, will be a contemporary meditation on Tule Canyon. It is the only canyon in the Caprock Canyon system that I have not spent time exploring.

- I am thrilled to see how the sensorial experience translates to music.

Creosote (On Everything)

- A long-form investigative essay on the political history and ecological impact of the ranching practices in West Texas, centered on the spread of the creosote bush.

Coyote Tongue

- A surreal mystery novel about a murder, spanning the absurd vastness of the southern High Plains. You’re in store for plenty of weird and horror filled vignettes to trigger your instinctive desire for the safety and familiarity of a milkshake. I’ll release each chapter as a serial sound-designed audiobook over the course of the year and will publish the written version as an e-book.