Notes From The Field Blog interview with Mary Roach, by Keli Hendricks

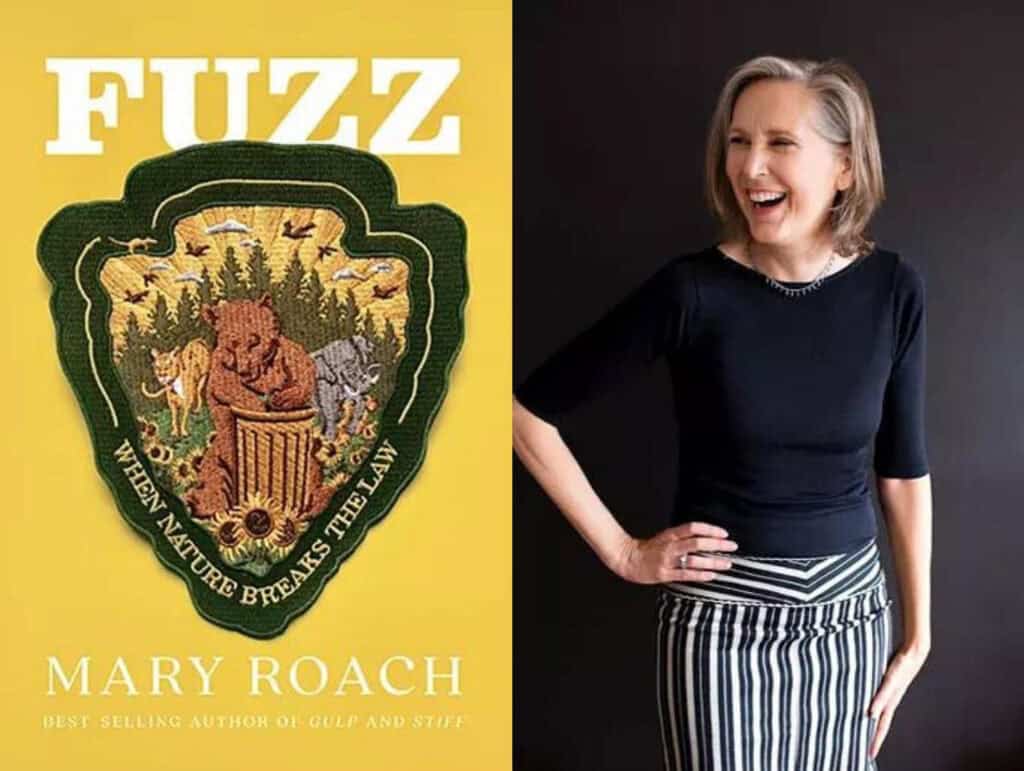

This week, Project Coyote’s Ranching with Wildlife Coordinator Keli Hendricks sits down to talk about all things wildlife coexistence with popular science writer Mary Roach about her new book: Fuzz: When Nature Breaks the Law.

Mary Roach is a New York Times best-selling author who is known for taking her readers on immersive dives into strange and sometimes gory subjects like cadavers (Stiff) and the digestive tract (Gulp), where she shares with readers captivating facts in her trademark entertaining and witty style.

Mary and I met in February 2018 when we both attended the Vertebrate Pest Conference (VPC) in Rohnert Park, California. As a fan of her work, I was excited to hear that she was doing research on a new book that would be diving into the world of human-wildlife conflicts, a book I felt would expose many people to a timely topic about which most know very little.

The classes offered at the VPC —topics like Will Zinc Phosphide-Coated Cabbage Allow for Effective Management of Belding’s Ground Squirrels? —might not appeal to the average layperson, and I was worried Mary might dump this topic and move onto greener, possibly more exciting, pastures. However, I underestimated Mary’s tenacity and her ability to find fascinating stories in the most unlikely of places.

When Mary’s new book hit the shelves, I read it right away. As someone who has been deeply entrenched in this complicated topic for years, I was impressed with the justice Mary gave this nuanced and complex subject. She shared her research in a way that will educate and entertain readers, regardless of their knowledge of the topic.

Mary agreed to answer my questions about her experiences writing Fuzz, and the journey on which her research took her.

Mary, thank you for agreeing to do this interview. Your books are all explorations into science-based subjects. Were you a science major in college, or how did these sorts of topics become of interest to you?

My pleasure, Keli! I took no science classes in college except for Astronomy 101, which I took because I’d heard it was an easy A. I can still name the four moons of Jupiter, although I hear by now they’ve found a half dozen other ones. I got interested in science through an early gig with an excellent magazine called Hippocrates, which dealt with health and the human body. At some point, an editor from Discover magazine contacted me about writing some features. Both of these gigs were tremendously enjoyable and by far the most interesting assignments I’d had as a magazine writer. That’s the path I started down, and I never had much reason to stray.

I’m guessing one of the most common questions you get asked about your books is: Why did you decide to write about this topic? So… why did you decide to write about human-wildlife conflicts?

I get excited when I stumble onto some pocket of science that I never knew existed. Human-wildlife conflict was one of those. Plus I’ve long felt it would be fun to write about animals in some manner, and I hadn’t come across any popular science books on this specific topic.

In the course of your research for Fuzz you traveled across the globe. What were some of the different cultural attitudes you found regarding human-wildlife conflicts? How do we in the U.S. compare to other countries in this regard? Are we more tolerant about living with wildlife or less?

I spent time in India with a researcher who helps communities deal with elephant conflicts in a humane manner. With elephants and monkeys, in particular, there’s a more accepting attitude that is tied in with these animals’ status within Hinduism. (The gods Ganesh and Hanuman appear as an elephant and monkey, respectively.) While people don’t believe the animals are literally gods, there is a reverence and a protective inclination — even though the animals sometimes create hardships for them.

We in the U.S. run a wide gamut. The divide mirrors the political divide, to the extent that it’s impossible to generalize about Americans. Some of us are quite tolerant and inclined toward coexistence, others seem to espouse the Manifest Destiny mindset of “subdue and conquer.”

One of my pet peeves is the fear-mongering that surrounds wild animals, especially carnivores, despite the minimal actual risks that the animals pose to us. My theory is that in America we are so removed from the natural world that these animals seem far more frightening to many people than they should. Do you think we exaggerate the risks posed to us by wildlife in America, and if so, do you think this could be a result of increased urbanization?

Yes, for sure. Though I think misconceptions fall into two camps these days, especially with regard to bears. There are people with ridiculously overblown fears of bear or cougar attacks, but there are also folks who’ve seen so many YouTube videos of bears being fed by people or hanging out on their decks etc., that they think it’s okay to walk up to a bear in, say, downtown Aspen, get out the selfie-stick and shoot a video.

Increased urbanization: Absolutely. When your experience of bears or coyotes or cougars comes from movies or YouTube, rather than knowledge and personal experience, you’re bound to get it wrong.

You wrote about the elephants in India which kill about 500 people a year. What I found interesting is what has been found to cause many of these conflicts. Can you tell us about that?

There’s been a tremendous amount of development across the so-called elephant corridor in the north of India, so much so that herds often get “pocketed” in small patches of forest, or they’re being forced to cross through villages and towns. Elephants are big; they eat a lot of vegetation and often find their way into farmers’ fields during the night. Understandably the farmers are upset, as they depend on these crops for survival. So what tends to happen is that people rush out of their homes with firecrackers or torches, and the elephants panic and scatter, and people get trampled. The researcher I traveled with helps set up Elephant Response Teams that come out in vehicles, which is safer, and herd the animals off the farmland as a group, which keeps them calmer.

In Italy, you spoke with an expert on ethics in wildlife conflicts. Do you feel that ethics are overlooked when it comes to our solutions to wildlife conflicts?

Yes. We have detailed protocols for the humane treatment of lab animals, but no such thing exists for conflict species. We leave it up to the pest control agents and wildlife control operators, who generally don’t give a lot of thought to the animals’ welfare.

What did you learn about the use of lethal controls as a method to solve wildlife conflicts?

Barring outright extermination, you won’t bring the population down, or not for long. Nature adjusts. Shoot one coyote or bear and another takes over its territory. Kill a few thousand squirrels and the ones that are left have more to eat. Which prompts bigger litters and shorter gestation periods. Etc. As one researcher put it, you’re just mowing the grass.

What are some of the interesting non-lethal solutions to preventing conflicts that you saw being used?

I like the boots-on-the-ground work being done: building more secure night-time enclosures for livestock, cutting brush back so mountain lions have nowhere to hide, altering grazing practices so members of the flock aren’t spread out. Automated nighttime lasers for bird dispersal seemed promising, though the safety of it, vis-á-vis bird vision, is a bit of a question still. But to me, the most promising solutions are those in the realm of encouraging coexistence: bringing ranchers, ag types, and wildlife advocates into sessions that are moderated by someone who knows how to keep things civil and productive. Getting people to listen to each other and to empathize, and then moving forward together, finding places to compromise and solutions both sides can accept.

What message, if any, did you hope people would take away from reading Fuzz?

A realization that in most of these situations, we’re the problem animal. And thus the most effective solution can be found in changing our behavior — not the animals’. I’d like people to think things through, to not simply call someone in to “deal with” conflict animals on their property, say. Take a look and see where the animal is getting in, and address that. Think about what you’re offering that animal to make your yard or home attractive, and take that away. Maybe the model should be closer to that of retail businesses: You don’t shoot shoplifters, you figure out ways to outsmart them.

To learn how you can help your community humanely coexist with wildlife, check out our new webpage of resources in collaboration with the National Animal Care and Control Association.

Many thanks to Mary Roach and Keli Hendricks for sitting down to discuss this important topic!