Notes From The Field Blog by Mack Cote, Project Coyote Programs & Campaigns Intern

The year is 2007 and it is spring or autumn or somewhere in between. I am a quiet girl and the white crescents of my fingernails are cemented with sweet dirt. My legs are covered in shallow scratches from a nagging underbrush, kneecaps dappled with the leaf litter that clings to my sweaty skin when I kneel. I am studying the configurations of plants and the cracks on rocks and the patterns in the songs of the birds around my home. Where I live there are white oaks and American elms and I wrap my long bony arms around their bodies, finding which ones I can hug fully, so that the tips of my fingers can just barely graze each other on the other side. I walk barefoot and I have some neighbor friends, but mostly my company is the ground under my toes and the trees against my chest.

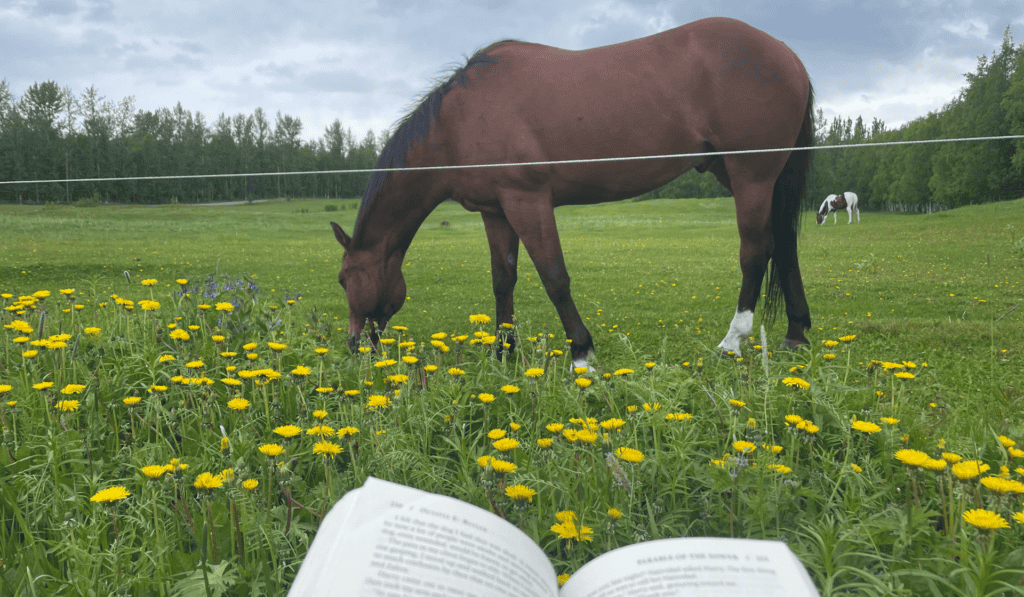

Photo by Mack Cote

I spend my time close to the ground, with a paperback chapter book: sometimes clutched in my small grip, sometimes flung onto the ground nearby. I’m reading Seekers or Warriors or something of the sort: animal worlds and stories and adventures. I am reading from the eyes of an animal, through the voice of an animal. I fantasize about being an intimate part of their world – talking with horses, flying with birds, sitting down to rest with the wolves. I imagine that I’m a member of their packs and herds and flocks alike. This is my early experience: right now I am small and so is this corner of my world, but the animals and plants and trees quietly tell me their stories.

Photo by Mack Cote

It’s now 2018 and early autumn in Madison, Wisconsin. It is my first day of college, and my first class of the morning. “Introduction to Wildlife Ecology” is in an old building with low ceilings and shaky elevators at the edge of campus, and my hot coffee has spilled all over my hand from the walk. It’s a tall building, busied with office spaces and research labs and is named after a Harry Russell someone. The classroom has faded walls and harsh white light and my laptop is cracked half-shut, overheating on my thighs under the desk.

The professor at the front of the room is talking about his life and his education and our lives and what they will be like here, in this tall old building. But my laptop is still overheating, my leg is shaking against my chair, and I can’t focus on what his voice is saying because there are hundreds of dead animals looking in at me with their black-marble eyes. Their lifeless bodies are nailed to the walls, hanging from the windows, perched in the cabinets, floating in jars filled with a chemical bath. Deer, pheasants, beavers, muskrats, weasels, skunks, shrews, badgers, foxes, squirrels, coyotes, snakes, bobcats. A bear skin hanging on the back wall under the broken analog clock. Frozen mouths and frozen faces. Stuffed with shavings and wool, propped into position: hunting, growling, crouching, sleeping. Something realistic. This is my experience; a man at the front of the room talking about his life, surrounded by dead animals with theirs sucked out of them- replaced with stuffing and plastics and chemicals and glass for eyes. Thus begins my journey into and my questioning of the field of wildlife ‘management’.

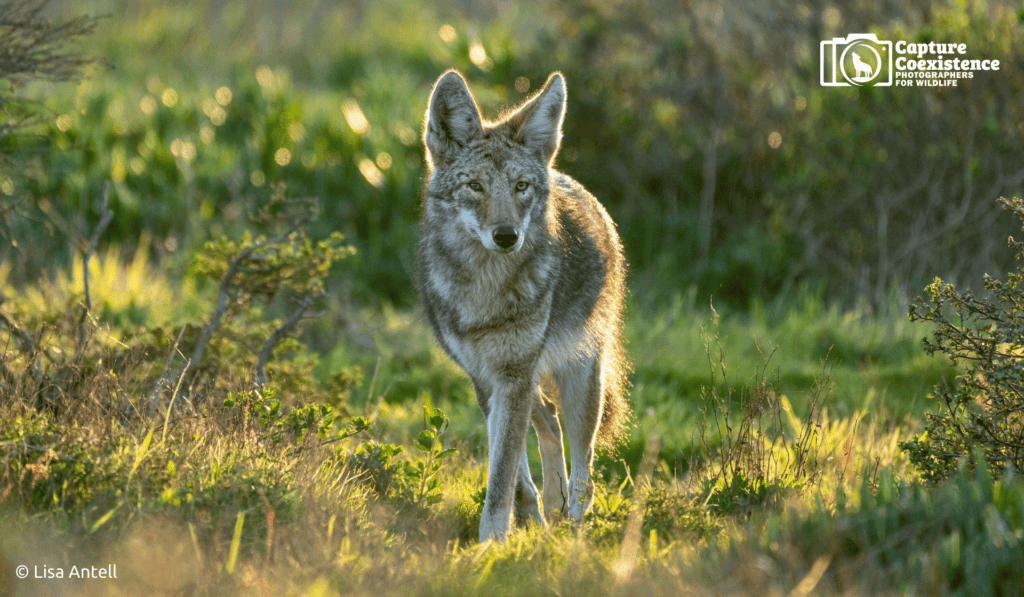

Photo by Lisa Antell, #CaptureCoexistence Contributor

Over the coming years, I will spend my time learning about wildlife ecology: population dynamics, behavioral ecology, resource partitioning, inter- and intraspecific competition, predation models, density dependence, conservation efforts during a raging climate crisis. I will memorize long Latin names for hundreds of birds and mammals and reptiles and amphibians. I will study their plumages and vocalizations and dentition patterns and skeletons and tracks and scat. I will hold a chipmunk in my gloved hand and feel her heart battering against her ribs and I will clamp a metal tag onto the edge of her papery-thin ear. I will whisper, I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m sorry. She won’t hear my words because how could she when my fist is closed around her body?

I will learn how humans can manipulate and control. My professors will tell me how it’s been done in the past, how it is being done now, and how it will be done in the future. I will notice the gaps. I will notice the most singular and loudest voice.

At the start of my third year, I enroll in “Caring for Nature in Native North America”, a course offered by the university’s American Indian & Indigenous Studies department. I am enamored and deeply impressioned by my professor – the materials she brings to class, the thoughtful content of our discussions, and the compassionate ways in which she speaks about the land and of wildlife species – or ‘nonhuman beings’. For the first time, I have the privilege to hear from a voice that has been left out of my previous curriculums. I am forming meaningful relationships to the content that I consume, and I question how the information was structured, who taught it to me, how it got to me, and what I am being told to do with it. I learn the preciousness of my choices. I learn the danger of perceived human power.

Photo by Heather Russell, #CaptureCoexistence Contributor

As I move through further American Indian & Indigenous Studies courses, I learn from various educators and peers. In my free time, I am swallowed whole by the work of Alexis Pauline Gumbs, Vanessa Watts, Max Liboiron, and Robin Wall Kimmerer. Their ideologies guide me as I peel apart that which now requires my unlearning.

In Robin Wall Kimmerer’s novel, Braiding Sweetgrass, she discusses how children are taught to speak grammatically correct in the English language. “When we tell them that a tree is not a who but an it, we make that maple an object; we put a barrier between us, absolving ourselves of moral responsibility and opening the door to exploitation” (Kimmerer 57). I think about my Wildlife Ecology courses and the language that my professors were so accustomed to using. Trees were ‘timber’, misunderstood species were ‘pests’, nonhuman beings were ‘wildlife’, seemingly untouched land was ‘wilderness’, and land stewardship and care was ‘management’. The common thread I noticed was a claim of superiority or a shift in responsibility. Kimmerer, among many other Indigenous scholars, guides the conversation in rethinking language and grammar.“If a maple is an it, we can take up the chain saw. If a maple is a her, we think twice” (Kimmerer 57). Animacy, an acknowledgment of spirit and sentience, allows for life to exist in language. It is common for English-speaking people to regard nonhumans as it, and while this may simply seem like a small grammatical rule, or maybe what just feels familiar, unrelated to one’s ethics and behaviors, it is working to uphold the very foundation that allows for exploitation and abuse of life. Not only is the maple seen as an it, but the maple is ‘timber’. ‘Timber’ negates the relationship with the tree, creating something new, and deems that new thing lifeless.

I think back to the stuffed deer and foxes and coyotes in the classroom. I think of taxidermy as an attempted space for connection – a place where people can easily access the beauty of beings that they wouldn’t be able to be close to otherwise. But there is no life here, and where there is no life there cannot be connection. I think of the constructs of ‘wildlife management’ as an attempt to connect, as well. But similarly, where there is domination and manipulation, there cannot be connection. There can only be a flattening of experience.

Photo by Matthijs Noome, #CaptureCoexistence Contributor

I think of coyotes, of foxes, of crows, of raccoons, of cougars. Pests, nuisances, they will call them. Species that, in most states across the country, have no hunting season or restrictions – ‘bag’ limits. Species that are targets of killing contests. The targets of fearful men with dangerous ideas. But if the coyote can be recognized as a being with an animated life, with agency in her choices, will she and all those like her still be murdered viciously? Lured with bait and predator-calling decoys? Ran through the engines of snowmobiles? Stacked in bloody piles by the masses? Will ‘agencies’ and ‘services’, and ‘managers’ and ‘troopers’ continue to condone these events? Will we turn away at the sight, or even just the idea, of her thoughtless death?

I think of my time as a child under the trees’ crowns. I think of the books that I read, the small observations I formed, my vivid imagination that kept me company. I am grateful for these young and curious moments. In them, I had begun to form the values that now guide me through my life. At this age, I was impressionable with a wide range for fantasies. Now, this naivety has been replaced with a more critical eye – one that recognizes and knows the weight of the colonialist, racist, and patriarchal industry that I engage with.

In Alexis Pauline Gumbs novel, Undrowned, she asks, “What is the scale of breathing? You are part of it now. You are not alone. And if the scale of breathing is collective, beyond species and sentience, so is the impact of drowning” (Gumbs 1). If this fate is shared, this existence must be shared too. It is time to listen. I think often of how I can remain inspired, hopeful, and energized. How I can be a part of, and even spark, the changes that are waiting. I believe it is important for us to have hard conversations with each other, and though they may leave us feeling deflated and disheartened, we must choose to stay soft. I can be angry and sharp and impassioned. I can also be slow and playful. This intersection guides me.

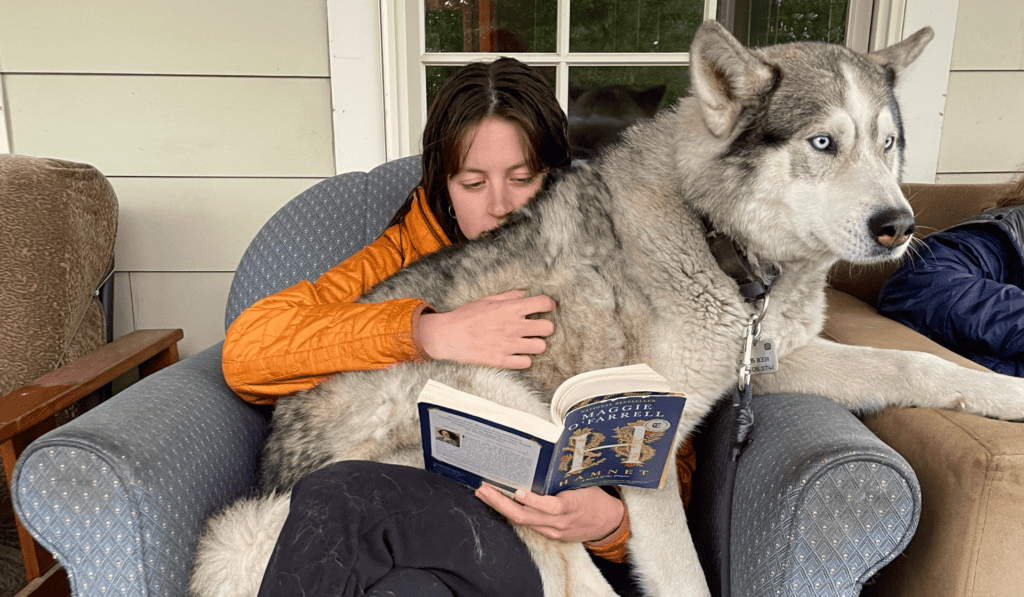

Photo by Mack Cote

I imagine being able to fly with birds, talk with horses, and sit with wolves. I hold these fantasies, these memories, close to my chest. But I also form new interactions, ones that aren’t so made-up anymore.

I watch the doe and her fawn loping cautiously through the forested swamps by my family’s home. I watch pelicans freefall into the wide and crashing ocean. I’m bathed in a salty chorus of treefrogs; there are too many to count and too small to see. I break for the tiny vole scuttling across an open road (dangerous, I know). I blanket the horses in a wintering barn, holding my numbed fingers to their muzzles to be warmed by their muggy breaths. I sit with my back pressed against the oak tree in the library’s courtyard. I hold the old donkey’s head in my arms and let him itch his forehead against my freshly-laundered blouse. I pause to hear the atmospheric bugling of the Sandhill crane.

And when I am perched outside on my rocking chair before bed (I am reading something, of course), I listen to the quiet rustling around my home. The thrushes are plinking melodically, back and forth to each other. I say, Goodnight thrushes. The fireweed is turning red and ablaze. I say, Goodnight fireweed. And though the space between us is hazed by dusk, their tall leafy bodies are waving back to me.

Literature Cited

Gumbs, Alexis. Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals. AK Press, 2020.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. “Asters and Goldenrod” and Learning the Grammar of Animacy”. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013.

Photo by Mack Cote

Mack Cote is a graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where she received her B.S. in Wildlife Ecology and a certificate in American Indian & Indigenous Studies. She is currently living and working in Palmer, Alaska, which occupies Dena’ina homelands. Mack is from Connecticut, where she grew up with a strong drive to care for and protect land and nonhuman beings. As a Project Coyote Summer 2023 Intern, she worked to develop Coyote Friendly Communities (CFC) Program toolkits.