Notes From The Field Blog by Renee Seacor, Project Coyote Carnivore Conservation Director

On Christmas day, a wolf strayed beyond Yellowstone National Park’s invisible northern boundary and was shot dead. My heart sank, wondering if it was the same wolf that peered my way and captured my attention just a month earlier.

I’d been standing in Yellowstone National Park at dawn with my partner when three wolves made their way over a hill and directly in our line of sight from our car. For a few moments, minutes, it was just us and wolves. They trotted along the roadside roughly 200 yards away. They paused and looked around, and each of them let out a few quiet, deep howls. Later, we’d try to piece together what they were searching for, what pack they were a part of, and where they were headed. We’d replay every single moment out loud to each other, again and again.

Yellowstone National Park wolf | photo by Renee Seacor

Yellowstone wolf sightings have always brought me immense gratitude over the years—getting to witness rare glimpses into the lives of wild wolves—but this time, I felt a new set of emotions: anxiety, stress, and deep concern for these wolves’ knowing full well what exists just a few miles north. The wolf management unit directly north of the park managed by Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks at that current moment had three wolves left in its quota, putting these three lives in direct danger. And they were wandering awfully close to the northern border.

The last time I was in the park was March of 2021, and again at dawn, I listened to the Junction Butte wolf pack howl in chorus from an elk kill site where the pack had been camped out for a few days. They were viewable from a pullout overlook off the north road, and we stood with an eager crowd of scientists, tourists, and full-time wolf watchers as we watched the pack through our spotting scope.

At that moment, the unprecedented slaughter of Yellowstone wolves and the egregious wolf killing across the entire state was brewing in the halls of the Montana Legislature but hadn’t yet begun. The Junction Butte pack who often stayed within park boundaries (roughly 96% of the time), had mostly escaped harm as residents of the park. But any semblance of protection or compassion halted abruptly in 2021 when Montana politicians sanctioned the killing of up to 85% of its state wolf population and removed the quotas previously in place for wolf killing on the northern boundary of the park. That season, our nation’s most treasured and iconic wolves were slaughtered one after another until 25 were dead, the deadliest season for Yellowstone National Park wolves in 100 years. That season across the state, 273 wolves would tragically lose their lives, wolf families were broken apart, and egregious practices like baiting, night hunting, and snaring legally took place.

Wolf tracks in Yellowstone | photo by Renee Seacor

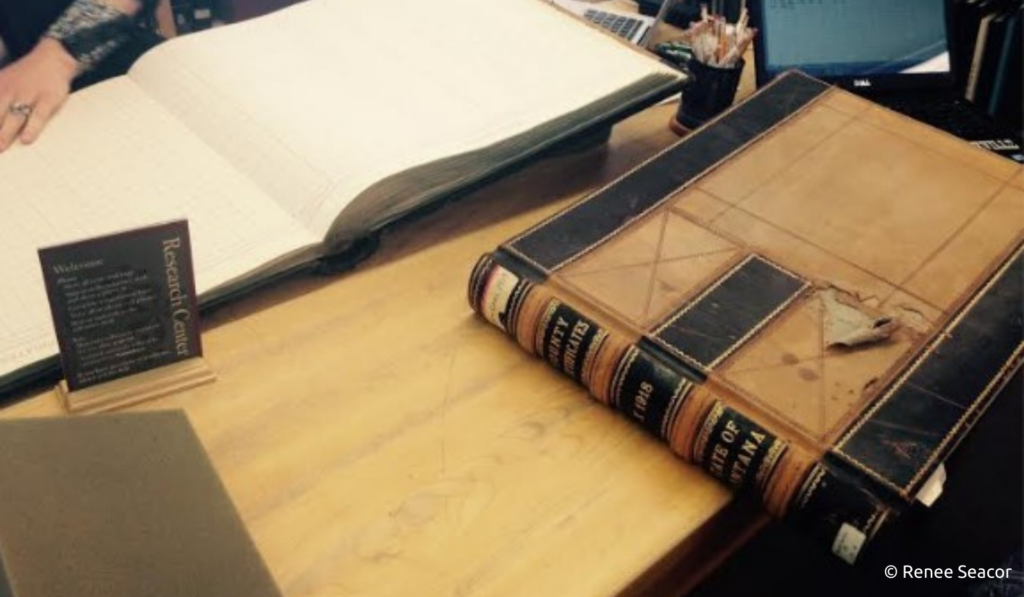

A sordid history

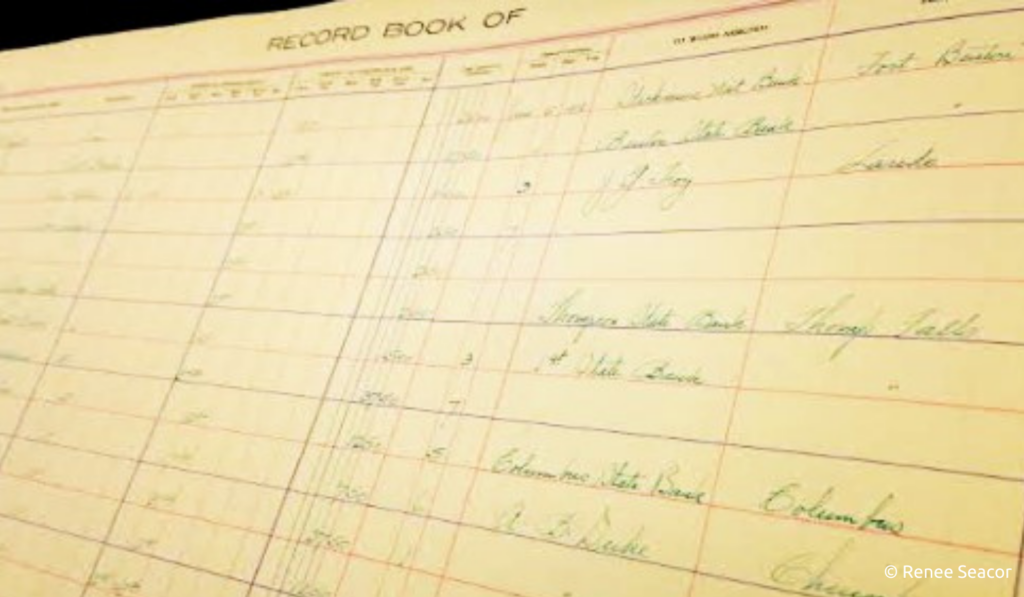

In 2012, I undertook a research project digitizing Montana Agricultural Commission records from 1892-1931 that recorded bounty certificates for carnivores killed across the state including wolves, coyotes, bears, and cougars. With every flip of a page, I recorded wolves by the tens, hundreds, and thousands that were ripped off the landscape and cashed in for anywhere from $3-$15. I struggled to understand the level of human savagery needed to fund the killing of a species into extinction, especially in contrast to my own personal desire to live alongside wild carnivores—a reason I chose to move to Montana in the first place.

Slowly as I progressed through the records, wolf kills started to shrink, and bounty hunters seemed to be bringing in less carnage until the number of certificates issued for wolves stopped appearing altogether. I remember the first few pages where wolf numbers disappeared, realizing I was staring at the ink marks representing the moment in time when hunters delivered the bodies of the last wolves to exist in the state. Bounty hunters slaughtered a species into extirpation and were paid by the state to do it. I had only recently learned the dark history of America’s war with wild carnivores, and something about the blank space on the page next to “wolf” as I flipped from 1927 onward made my heart heavy and my head spin. Naively, I remember thinking (hoping) that level of human hatred toward carnivores was surely a thing of the past?

Montana Agricultural Commission records | photo by Renee Seacor

I’d get back to Billings, where I was attending school at Rocky Mountain College, and promptly grabbed a beer with a friend whose family owned a ranch outside Lewiston, Montana. I tried to better understand the root of such strong emotions toward wolves and conversations like those would make me feel that all conflicts could be settled over a beer. But unfortunately, I’d also learn the realities of age old anti-predator hysteria used to support political extremism and minority special interest groups. The truth is the majority of the public doesn’t want to kill wolves, less than .02% of Montanans hunt and trap wolves. Instead, wolves and their killing have turned into political pawns and represent the ideologies of a few extreme politicians.

The divisiveness that has spread across the country in recent years, that we’ve all borne witness to, has also torn up wolves in its wake. The minority participates in the unjustified slaughter of wolves to the detriment of the majority, who benefit from healthy ecosystems and revel in the beauty of getting to share a landscape with such a unique and intrinsically valuable species.

As it turned out, the year before I began digitizing wolf bounty records (2011) was the year Senator John Tester attached a federal appropriations rider to a must-vote budget bill that would remove Endangered Species Act protections for wolves in the Northern Rockies and direct management back to the states of Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho. Slowly the hunting and trapping of wolves would ramp up and up, killing begetting more killing. And even the bounty payments that I had prayed were a remnant of a dark past began again. With states like Idaho allocating over $200,000 to pay bounties to hunters who killed wolves.

Record of bounty certificates for carnivores killed across Montana | photo by Renee Seacor

Our fight in defense of Montana’s wolves

This is why Project Coyote, along with co-plaintiff WildEarth Guardians, sued the state of Montana in November of 2022 over their extreme anti-wolf hunting and trapping policies, and why despite countless attempts by the state to dismiss the case we wage on, in defense of wolves.

Among legal arguments, our suit lays out why recent wolf policies violate the state constitution which protects wildlife as a public trust resource for all Montanans—and not just the fringe minority who participate in the unethical slaughter of wolves. Triumphantly the state of Montana’s constitutional duty to protect the environment for present and future generations was just reaffirmed in Held v. Montana. In Held, a judge ruled that the state’s failure to consider climate change when approving fossil fuel projects was unconstitutional.

Montana’s rugged Northern Rocky Mountain landscape | photo by Renee Seacor

Wildlife is also held in the public trust, and therefore Montana has a positive duty as public trustees to manage their wildlife, including gray wolves, for the benefit of all Montanans. At a very minimum this requires transparent, scientifically defensible management strategies that preserve rather than diminish or imperil the species.

In defending our case in November of 2022, we called on the state to recognize the intrinsic, economic, cultural, and ecological value of wolves and the outsized benefits they provide across our communities. For some of Yellowstone’s wolves, entire books have been written about individuals, their unique personalities, family lineages, and relationships. Some of those treasured individuals have been killed because of Montana’s shortsighted policies, and eulogies tragically written in their names.

My most recent trip to Yellowstone just a few months ago reminded me yet again of the critical importance of our continued litigation in Montana and our advocacy in defense of all canids nationwide. Hours after getting to observe three Yellowstone wolves, I laid awake in our Airbnb in Gardiner, breath still cold from the November air. I wondered if, at that very moment, those wolves were venturing far too close to danger—the human hatred that sat just outside park boundaries. I thought about the countless wolves unknown to me across the state, who aren’t afforded the protection of living in or close to a National Park. We continue our fight in the courtroom for all of them.

Renee Seacor in the backcountry

Renee Seacor is an interdisciplinary environmental advocate with a background in wildlife ecology and environmental law and policy who has dedicated her professional career to using science-based advocacy to guide and develop policy solutions to challenging conservation issues. She currently serves as the Carnivore Conservation Manager for Project Coyote, where she advocates for the conservation of carnivores through science-driven advocacy.